Foreword

The Impossible Press

About Jay Rosen's 1986 PhD dissertation

In the summer of 1980 I moved to New York City to become a press critic. I was 24. I had no connections.

In their place were these advantages:

I thought I was a good enough writer, but I also knew that I was poorly read. Basically nothing about the world beyond the newspapers and magazines that I was then scouring. (Remember: no internet.) I call this an advantage because the thrills of discovery made it easy for me to read and take notes all day and all night.

NYU had a masters and PhD program called "Media Ecology." Perfect! I could solve my "poorly read" problem with NYU professors as a guide. "Media ecology" felt exactly right for what I wanted to do as a writer.

I had a strategy that turned out to be the right one. Instead of becoming an academic or a journalist I would try to find my voice between these identities, friendly to both, but with some distance as well.

I had a good way to get started. "Take as many courses as you can from Neil Postman."

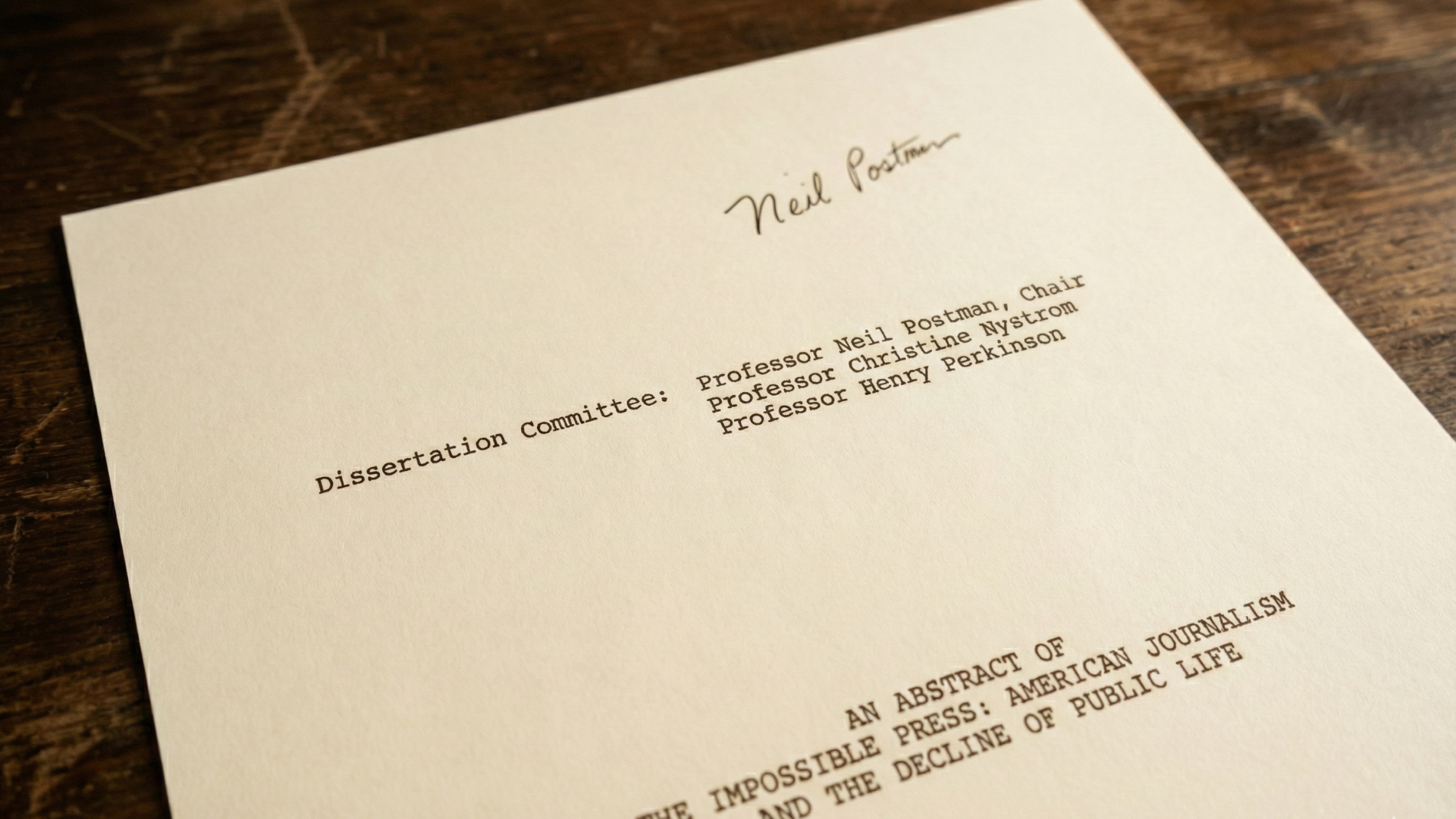

Postman! Founder of the Media Ecology program at NYU and one of our best cultural critics, then working on Amusing Ourselves to Death, his best and most famous book, translated into 16 languages. He became a model for me as a teacher, speaker, writer, and public figure. (You can read about Neil and I, teacher and student, here.)

Of course they won't give you a PhD just for taking courses, reading a lot of books to catch up, and drinking wine with your teachers after class. You have to make an original contribution. You have to research and write a work of your own, and it has to meet your professors' standards. Ideally these are high, but not unreachable.

Here I gave myself a further goal, again inspired by Postman. It was to write for what used to be called the "common reader," a phrase rarely heard these days. Roughly it means, "No need to learn a new language to understand the book." Basic literacy will suffice.

Normal dissertations are not like that. They exist within a scholarly discourse divided into sub disciplines that are built to handle small but (we hope...) meaningful advances in our knowledge.

I wanted to try something else. My first serious work of press criticism would be spread across a big landscape, from why we needed journalists in the first place (the answer lies in the scale at which modern life is lived) to prospects for an informed public in the crowded media environment of today.

The dissertation I submitted to NYU began to emerge for me when I came across a now famous exchange between Walter Lippmann in his classic book, Public Opinion (1922), and John Dewey in his classic reply, The Public and its Problems (1927).

Lippmann doubted there could be a news-reading public in the way we normally thought: a public consuming quality journalism to inform itself and make sound decisions. We have to abandon those expectations, he said. Among the factors they failed to reckon with: the attention market and all the distractions it comes with.

John Dewey took the point about attention, but drew a different conclusion. Discard any hope for an informed and engaged public and you run the risk of ditching democracy altogether. Are you sure you want to do that? We have to keep trying with the tools we have, Dewey thought. If the press can't help us then we need a better press!

By careful study of this debate I got the idea for my dissertation. It would be the history of an idea: The press informs the public and that makes democracy work. Where did this idea come from? Does it still apply? What work does it do? And who was right: Lippmann or Dewey?

I chose the title, The Impossible Press, to underline key observations like this:

"With every improvement in the delivery of information comes a new level of difficulty for citizens seeking to understand their world. No doubt this is one reason why we so often seem to have more information and yet be less informed."

The Impossible Press, p. 390

To wrap up. Today I am putting my dissertation online, with the help of web producer Joe Amditis, who built the site with all of its features, and Samuel Earle, PhD candidate at Columbia Journalism School, who is currently writing his own dissertation about our renewed interest in crowds. You can find his essay, comparing his work to mine, here.

Putting "The Impossible Press" online is part of a much larger project, The Jay Rosen Internet Archive, which Joe Amditis and I plan to release in February, 2026. These are the kinds of things I imagined doing when I retired from NYU earlier this year.

I have been publishing my work online since 1996. So I know that a dissertation from some 40 years ago is not going to have a huge or immediate audience. But that does not bother me. People who might have an interest in what we did here include...

- ✦ Fans of my writing over the years. There are some.

- ✦ PhD students who are working on dissertations themselves, or who finished one recently.

- ✦ Professors who want (or already have) a digital archive of their own.

- ✦ Web developers working with academics.