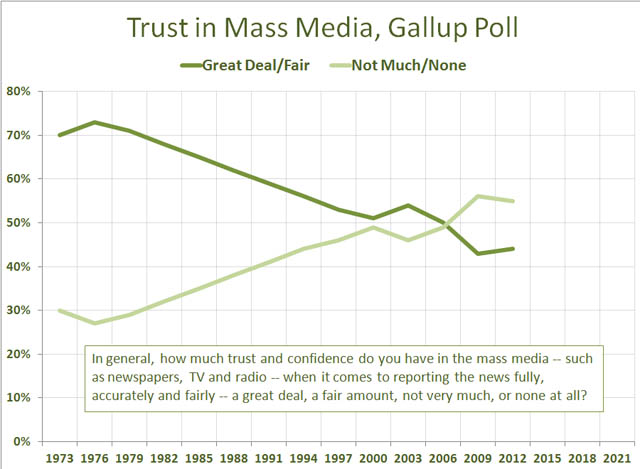

The percentage of Americans who had a “great deal” or a “fair amount” of trust in the news media has declined from over 70 percent shortly after Watergate to about 44 percent today.

Why? That is my question here.

It’s a puzzle because during that same period several other things were happening. Journalists were becoming better educated. They were more likely to go to journalism school, my institution. During this period, the cultural cachet of being a journalist was on the rise. Newsrooms were getting bigger, too: more boots on the ground to cover the news. Journalism was becoming less of a trade, more of a profession. Most people who study the press would say that the influence of professional standards, such as we find in this code, was rising.

So the puzzle is: how do these things fit together? More of a profession, more educated people going into journalism, a more desirable career, greater cultural standing (although never great pay) bigger staffs, more people to do the work … and the result of all that is less trust.

Why?

Let me be clear: I’m not saying there’s no explanation, or that this is some baffling paradox. Only that it’s worth thinking through how these things fit together. (For more on declining public confidence see this overview from 2005.) Here are some possible answers:

When you put the trust puzzler to professional journalists (and I have) they tend to give two replies:

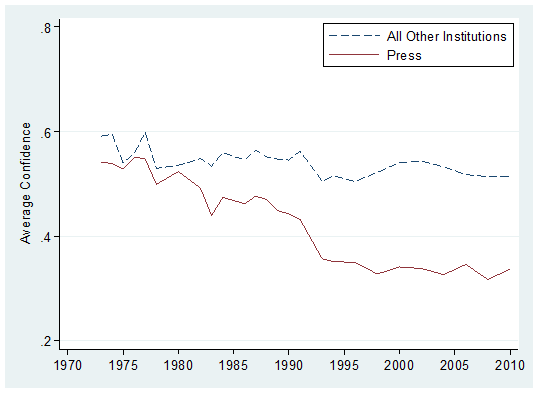

1. All institutions are less trusted. The press is just part of the trend. Here are a few comparison figures from Gallup’s confidence surveys (Pdf):

The Church. In 1973, 66 percent had a great deal or a fair amount of trust. 2010: 48 percent.

Banks. 1979: 60 percent, 2010: 23 percent.

Public schools. 1973: 58 percent, 2010: 34 percent

The Presidency: 1973: 52 percent, 2010: 36 percent

The problem with this answer is that it ignores the whole idea of a watchdog press. If these other institutions are screwing up, or becoming less responsive, then journalists should be the ones telling us about it, right? Suppose the Catholic Church fails (scandalously) to deal with child abusers among its priests. If journalists help expose that, confidence in the press should rise. That’s the watchdog concept in action. Big institutions are less trusted. But in itself that doesn’t explain falling confidence in the press. Public service journalism is supposed to be a check on those institutions.

2. Bad actors. The second answer I hear the most from journalists is that bad actors–especially the squabblers on cable television, and the tabloid media generally–are undermining confidence in the press as a whole. Just as Americans hate Congress but tend to love their local Congress person, they can’t stand “the media” — as reflected in your chart, Jay — but they feel differently about their own habitual sources of news. (Go here for some evidence of that.)

From this point of view, there’s no trust problem at all, really, just a category mistake. The most visible news people are being mistaken for the whole institution. If we could stop doing that, there wouldn’t be any drop in confidence.

The conservative movement has an answer to my question, which they try to drill into my head whenever they can:

3. Liberal bias. The United States is a conservative country (center-right, as radio host Hugh Hewitt likes to say) but most journalists are liberals. Even though they claim to practice neutrality, they weave their ideology into their reporting and people sense this bias. The result is mistrust. The problem has gotten worse since 1976. What else do you need to know?

Well, one thing I’d like to know is: how come Fox News, dedicated to eradicating liberal bias, is simultaneously the most mistrusted and the most trusted news source, according to survey research. That suggests it’s a little more complicated than: conservative country, liberal press. Wouldn’t it make more sense to begin like this? The United States is a divided country…

The political left has a different answer to my question. I should point out that it is not analogous to the right’s answer:

4. Working the refs. The right has learned how to manipulate journalists by never letting up on the “liberal bias” charge, no matter what. This amounts to working the refs, in Eric Alterman’s phrase. In basketball, some coaches will as a matter of course complain that the referees are favoring the other team. Their hope is to sow confusion in the minds of the officials, and perhaps get the benefit of the doubt on some calls.

Working the refs is indifferent to the actual distribution of judgment calls. Coaches who believe in the method use it regardless of whether the refs have been unfair (or generous) to their side. The aim is to intimidate. In the degree that “working the refs” works, journalists favor the side that is complaining the most. This amounts to a distortion of the picture presented to the public. From that distortion, mistrust follows.

But is it really true that the left does not know how to complain about bad calls, while the right screams at every opportunity? Maybe in 1969, when Spiro Agnew’s complaints began, that was so. It hasn’t been so for a while. This complicates the case.

My own theory, which I do not see as complete or even adequate.

5. Something went awry. My own sense is that the loss in confidence in the press has to do with professionalization itself. There was something missing or out of alignment in the ideas and ideals that mainstream journalism adopted when it began to think of itself as a profession starting in the 1920s. Whether it was newsroom objectivity, or the View from Nowhere, the production of innocence, the era of omniscience, the Voice of God, or the claim to provide “all the news,” whether it was the news tribe understood as a priesthood, monopoly status for metropolitan journalism, the identification with insiders, or an underlying media system that ran one way, in a one-to-many or broadcasting pattern… I don’t know. Maybe all those things.

I haven’t figured it out yet (in fact, much of my writing at PressThink has been an attempt to think this through…) but it strikes me that something went awry within the professional project–which also did a lot of good for journalism–and eventually that flaw began to take its toll on public confidence. The press got out of alignment with its public, and mistaken ideas that weren’t seen as mistaken prevented self-correction, resulting in symptoms like this.

The first addition based on a number of comments I received since this was posted.

6. Just part of the power structure now. Over Twitter, investigative journalist Phil Williams wrote, “Press more popular when viewed as standing up to power. Then it became part of power structure.” From this point of view, the glamorization of journalism after Watergate, combined with the influence of celebrity within the news tribe, plus the growing concentration of media ownership in a few large companies that themselves seek influence, had made mockery of the journalist as a courageous truthteller standing outside the halls of power.

Ground zero for this explanation would be the annual White House Correspondents Association dinner, in which all the factors I just mentioned are on vivid display.

I’ve been blogging at PressThink since 2003. The comment thread at this post may be the best since I started. Nos. 7-8 derive from it.

7. Culture war! Let’s say 20 percent of the country buys No. 3: liberal bias, 20 percent buys No. 4: working the refs, and 10 percent is ready to tear its hair out with the professional journalists’s imaginary solution: “he said, she said” reporting. (These, I think, are conservative estimates.) Put them together and half the country is angry at the press before it gets its boots on.

Like I said, America is a divided country. There’s a seductive pull to placing yourself in the middle between what you imagine to be “the extremes.” That seems like the safest position, but is it really? The trust figures suggest the answer is: no, not really. Have you heard CNN’s slogan for its 2012 election coverage? “The only side we’re on is yours.” But it’s just a slogan. CNN has no idea how to make it real.

8. Too big to tell. In the comments, John Paton, the CEO of Digital First Media, second largest newspaper company in the U.S. (Disclosure: I was for a time a paid advisor to this company) speculates:

Society has profoundly changed in the last three decades.

The factors are many: economics; wealth; job security and empowerment. Technology empowers but real power to change one’s life is perhaps even further outside of most people’s grasp than before – i.e. Job expectations; education expectations; home ownership expectations; upward mobility, etc.

If there is a growing awareness of those disconnects, then perhaps society understands that the news media has failed them on the bigger issues and no amount of exposing corrupt politicians and thieving captains of industry will let the news media regain that trust.

According to this interpretation, stories that are “too big to tell” (not that they literally could not be told but they overwhelm journalism as it stands today…) are the ones that have really affected people’s lives. For example: “real power to change one’s life is perhaps even further outside of most people’s grasp than before.” Intuitively, the audience understands that journalists are never going to tell them “what’s going on” in the largest sense of that phrase. And this takes its toll on trust.

None of these explanations quite do it for me. I think they all have some merit, but “some” does not mean equal. I’m partial to no. 5, but I don’t think it accounts for a 28 point drop in public confidence. So that’s why I say: what would be your theory?

After Matter: Notes, Reactions & Links…

Sep. 17, 2014: Gallup: Trust in Mass Media Returns to All-Time Low. Six point drops in trust among Democrats and Republicans.

August 8, 2013: Pew Research Center returns to the subject:

Public evaluations of news organizations’ performance on key measures such as accuracy, fairness and independence remain mired near all-time lows. But there is a bright spot among these otherwise gloomy ratings: broad majorities continue to say the press acts as a watchdog by preventing political leaders from doing things that should not be done, a view that is as widely held today as at any point over the past three decades.

Aug. 16, 2012: Pew Research Center comes out with a new report: Further Decline in Credibility Ratings for Most News Organizations:

For the second time in a decade, the believability ratings for major news organizations have suffered broad-based declines. In the new survey, positive believability ratings have fallen significantly for nine of 13 news organizations tested. This follows a similar downturn in positive believability ratings that occurred between 2002 and 2004.

The Washington Post’s Ezra Klein takes up my puzzle:

I think you should see #3 and #4 as mirror images: One is the argument the right has used to erode trust in the press. The other is the argument the left has used to erode trust in the press. Both, it should be said, have their roots in real events and real grievances. The rush to war really was an example of the media — including me, as a dumb blogger in college — getting worked. But both are also the result of organized campaigns to take those real events and real grievances and turn them into a durable distrust of the media that can be activated when convenient for the two parties.

That doesn’t mean Republicans or Democrats have stopped reading, or caring about, the news media. Indeed, the loss of trust in the press has, as I understand it, coincided with a rise in the actual consumption of news media. I think we should take that revealed consumer preference for more news and news-like goods at least as seriously as we should take these poll numbers. The parties certainly do. That’s why, rather than trying to persuade their folks to abandon the media, they have contented themselves with trying to persuade them to simply mistrust the media.

Responding to both me and Ezra Klein is political scientist Jonathan Ladd: Why Don’t People Trust the Media Anymore?

I see two structural trends coming from outside of journalism as the main drivers of media distrust. First, the political parties have become much more polarized in their policy positions. Second, because of technological changes such as the rise of cable and the internet, as well as regulatory changes such as the end of the fairness doctrine, the media industry has become much more diverse and fragmented.

He also includes this chart showing the long-term decline in trust for the press as against other institutions:

One thing I don’t understand in Ladd’s post is this part: “I tend to be skeptical of any explanation for broad change that hinges of human nature simply improving or degrading. I suspect that human nature tends to be constant. Instead, I look for structural explanations. (Thus, I disagree with Rosen’s explanations #2, 3, 5, 6, and 8.)”

Human nature? I don’t get it. I don’t see how these explanations derive from a claim that human nature changed after Watergate, which is indeed absurd and unconvincing.

Ladd responds: “What I was trying to say was that journalists haven’t simply developed a greater natural propensity to behave like ‘bad actors,’ or exhibit bias, or be out of touch with the public, or co-opted by elites, or to miss scandals (like the Jayson Blair scandal) for too long, or exhibit other behaviors that we as observers might fault them for.”

Part two of Ladd’s post: Why It Matters that People Distrust the Media. Indeed.

Craig Silverman author of Regret the Error, and a student of trust construction in journalism, replies to this post with: Connecting the dots: Why doesn’t the public trust the press anymore?

Journalism that acts as the voice of God, that doesn’t listen, that doesn’t admit failings, that often punishes others for showing vulnerability does not build connection with the public.

Poynter’s resident sage, Roy Peter Clark, organized a chat with me and Craig Silverman: What can writers do to build the public’s trust in the media? The main point I tried to make is that the means for generating trust must themselves evolve.

In the comments: Clay Shirky, John Paton, Marcy Wheeler, Jeff Jarvis, Tom Watson, John Robinson, Chris Anderson, Andrew Tyndall, Roy Peter Clark and a whole lot more. Best comment thread I’ve have ever had at PressThink. (Not joking.)

The Washington Post’s Paul Farhi takes on a similar subject, but his point seems to be that there’s nothing to see here, so move along: How biased are the media, really? Not much, he seems to say, so why do people tell pollsters the opposite? He then lists possible explanations, which resemble some of mine.

James Fallows in 1996: Why Americans Hate the Media.

√ Public Trust in Government: 1958-2010.

Christopher Lydon–journalist, intellectual, radio host, and Boston presence–interviewed me when I was in Cambridge about the declining faith in American institutions, including the press. Because he is so good at what he does, it is one of the best interviews I’ve done in many years, and very much on point for this post. It will cost you 35 minutes to listen to it.

National Journal: In Nothing We Trust: Americans are losing faith in the institutions that made this country great. Loss of confidence in our major institutions is typically a social science subject. Here is a journalistic treatment that is quite good.

Clay Shirky argues that what was called “trust” in the Cronkite era was really just scarcity. And now that’s over.

Gallup chart by Terry Heaton’s PoMo blog and Audience Research & Development LLC.

267 Comments

Alternative media sources provide a richer and more varied perspective than mainstream media, whose channels come off as clones, using the same footage and repeating press releases practically verbatim. In the end, it’s just as easy to tap online sources as is to turn on a scheduled program or wait for the newsweekly.

Thanks, Victoria.

The problem is that 20 points of the 28 point drop in confidence had already been lost by the time the World Wide Web and its riches came into Americans’ lives. Doesn’t mean your factor isn’t a factor, but we need more than it.

Hmm… In that case, could the trust problem be related to anti-intellectual attitudes as well? The association of leftism with level of education, however false, was very strong in the seventies and the right has continued to milk it.

I think you’ve noted what is a continuing thread in American cultural history, Victoria. “Know-nothing” and “all opinions are equal” is an anti-intellectual theme which today plays out through aegis of most notably Fox News amplifying what the GOP has used as a political tool at least since Nixon’s era. The press role in the Bush/Gore election added in the likeability factor of “W” being a guy you’d like to have a beer with..the “C” student…vs. his fellow Harvard grad opponet as a “stiff” and “nerdy” policy “wonk.”

As the practice of journalism by “journalists” has become more transparent/accessible to citizens, citizens have become more skeptical of the practice’s claim on authority/credibility. Citizens increasingly intuit that the practice of journalism doesn’t reflect “truth”, it alludes to/creates “truth.” They’re learning how the sausage is made. The good thing (maybe): Citizens are increasingly interrogating the “truth” resulting from journalism and—to do this well—they need more “truths” to interrogate.

I agree. People have access to much more information — some good, some bad, much misleading — that they then use to evaluate what the mainstream media is telling them. Some realize that the gatekeepers are filtering out information that is important to them. Some realize how arbitrary the whole editorial process can be. For others, getting information from generalists who are prone to understandable but dumb mistakes no longer is sufficient. Journalists are no better or worse than they have ever been, but their readers now know more than they ever have before regarding the raw materials everyone is working from.

As Jay pointed out in the post before these two, Web20 and this transparency stuff is pretty darn recent. But the decline in trust began more than 30 years ago.

Refering to growth of cable news. Used to watch dad hand-crank sat dish too CNN. Remember him critiquing wire copy in local paper vs. CNN. .

30 years ago, eh? Hmmm, what was the most significant shift 30 years ago?

Reagan deregulation of media monopoly ownership rules? Devastated the rural landscape, radio, small papers, to the obliviousness of the metro-myopic press. Took a bit of time for the effects of massive media monopolies and “this town ain’t big enough for the two of us” newspaper wars to reach the “coasts.”

To the point that an entire generation of radio journalism grads in the 80s never worked one day in their fields. Rural radio, even essential weather reports, was replaced with taped repeaters.

But one overlooked effect of the massive corporate 30% profit-machine buy-in to siphoning ad money out of communities and out to shareholders while constantly hollowing out and cutting news staff is this:

Truth-telling was no longer within the majority of the news staff’s pay grade.

To write authority-challenging truths, you had to be WAY up the management totem pole, top managing editor, at least. That was something they didn’t tell me to expect in journalism school, while I dreamed of being Woodstein.

Sure, salaries were always kept low. But newsrooms were radically destabilized by a climate of constant layoffs and the disappearance of veteran reporters and editors (higher paid, more likely to challenge corporate management, must be let go).

But worse than that, the corporate carpet-bagging masters had the only game in town, often the only game in many towns. They governed the system that determined if you’d ever be able to work in that field again.

Overt censorship or self-censorship, I’ve lived under it. Even during the early Iraq War, I was forced, by my relative unimportance in the newsroom, from reporting actual true and multiple-source verified facts about Iraq and WMD, not because anyone told me not to (no one did), but because the party line in favor of the US govt position on everything was such that one couldn’t even call into question the tightness of President Bush’s codpiece in the “Mission Accomplished” aircraft carrier landing and not risk instant dismissal.

Your editors would catch it and take it out anyway. You could try to sneak things past them, like on cable news headline “crawls”– blind spots that don’t usually get copy-edited. But if someone saw it, you’d be out.

To break ranks, to break “voice,” that monolithic US mainstream media voice, was career suicide.

I agree totally! The deregulation and merger of radio TV and newspaper ownership made it much more difficult for reporters to get out there anything that went against “the powers that be”. Eventually the public caught on to this fact, that the media is pretty much a corporate mouthpiece, and their trust evaporated,

Chris Boese

Well said.

I agree.

To me, all of the points Jay enumerates result from the commercialization, corporatization and conglomeration of media outlets started under President Reagan’s administration and which you so well describe.

To me, it’s pretty simple, so here are my takes on Jay’s .

1. That all institutions are less trusted does not mean that they are all less trusted for the same reason. I would posit that many are because the corporate control of all institutions has increased drastically over the last 30 years. And thus, the purpose of each institution has been subsumed to the needs of corporatiions.

Specifically:

a. Banks have been allowed to gamble (with increasing stakes) at will with people’s money. When the gamble pays off, they talk about how great and worthy they are. When the gamble doesn’t pay off, the politicians who are beholden to them allow them to get off scott free legally and financially. As added insult, they force the same people who lost their money in the banks’ gambles to pay for the banks’ losses.

b. Public schools have always, to some extent, been there to create employees rather than critical thinkers. The vilification of teachers, as well as the demonization of under-performing children has led to a test-driven education system that makes it increasingly difficult for a teacher to create critical thinkers. In addition, the [mis]justification of privatization of schools as a panacea not only perpetuates this, it creates an arena within which corporations can transfer taxpayer money to private coffers.

c. The increased power of corporations over the presidency is self-evident. The breaking of campaign promises is expected. The indemnification of corporate bad acts is routine. The military machine has gotten so large that it needs wars to survive and presidents of both parties oblige. The erosion of the constitution and civil rights is commonplace.

d. The church has had its own problems and scandals so it is natural for people to have less trust in it. But even here the whole “Christians have a right to be rich and be proud of it” in some churches has become the driving force in some churches and all but drown out the commonly-thought of Christian virtues of of prudence, justice, restraint, fortitude, faith, hope love and charity. Not to mention that the holy virtues are supposed to be attained through selfless pursuits.

2. Bad actors work for and are the executors of the greater control exercised by the powerful over the message which is acceptable to be transmitted to the populace.

3. Journalism, in order to fulfill its mission of helping the largest number of people possible to make informed decisions, is inherently populist. Those beholden to corporate America misrepresent populism as liberalism and so influence conservatives to subsume facts and truth to the party line. They thus convince people to support causes NOT in their best interest.

4. Working the refs: When corporations centrally own so many media outlets, it is easy to coordinate a message and get the audience to not pay attention to facts or truth. Or even care about them.

5. I agree with Jay on something happening when the trade became a profession. It seems to me that when it was a trade, more people practices it with integrity. And, though many lists of the principles of the profession and the ethics of the profession have been developed in the last 30 years, it seems to me that the corporate journalist media have developed them more to create the appearance of integrity and to explain why “In this case, that principle doesn’t apply” [similar to the way journalists have contributed to the erosion of the constitution and civil rights by NOT, as a group, raising any kind of fuss about it] than to actually live up to them. I put little of the blame on journalists as individuals. It is difficult to not live up to the unstated conditions of your employment, as Chris Boese shows us above.

6. Corporate “journalists” value having access to power more than telling the truth (and ESPECIALLY more than telling truth to that power). They also dismiss criticism of their work as people not really knowing what’s going on. And so, people lose their trust in the press.

7. As I alluded to in 3, corporate journalism is a contributing factor in creating the class wars that those in power create so that they can go about their business while the rest of the country fights self-defeating battles against artificial enemies. American is a dividing country because journalism is allowing it to be so by not exposing the fabricated divisions between people of common interest.

8.I think the “too big to tell” is not only a self-justifying explanation, but one which can be invoked to justify smaller and smaller stories because they can be thought of as being part of that “too big” story. I am surprised by the cynicism of the audience reflected in Jay’s saying “the audience understands that journalists are never going to tell them “what’s going on” in the largest sense of that phrase.” It is a journalists job to tell the truth as accurately and thoroughly as possible, It they feel it is “too big to tell”, the answer is NOT to not tell it; the answer is to tell it in a way that the most people will be able to take it in.

Excellent and accurate, Christopher Krug. If someone like you started a blog, I would subscribe. It won’t happen because those in the press are not ‘real’ people with normal observations. They are very obviously corporate shills, touting the party line. Whatever happened to investigative journalism? It died along with JFK. The majority of the public has figured it out – and can’t trust a word out of the mouths of the major networks.

Professionalization creates a perceived loss in everyman status. Once a person/position is elevated, the mistakes become glaring and harder to forgive. I think it’s a mix of #1 and #5.

Right, Katie. There is a big difference between “this is the best we could do in figuring out what happened today” and “that’s the way it is.” The first claim stands a chance of being believed over a long period of time. The second does not. One of the strange things about trust is that it’s related to how much you claim for yourself.

Years ago I saw a zine whose corrections were headed “Things we learned after the last issue was printed.” It struck me as a nice humble way to not claim too much.

Phil Williams on Twitter:

“My theory, @jayrosen_nyu: Press more popular when viewed as standing up to power. Then it became part of power structure.”

https://twitter.com/#!/NC5PhilWilliams/status/192460976342302721

(Williams bio: Chief investigative reporter, WTVF, Nashville. Recipient: duPont, Peabody and George Polk awards, Pulitzer finalist.)

Absolutely. I was honestly surprised when I read down your list that this wasn’t mentioned. While the concept of the watchdog press is still lumbering along like a zombie, I feel the perception is that the press stopped speaking truth to power long ago.

Sure there are moments when the zombie shows some life. But when “embedded” reporters report from a war zone, or the press seems to do no more than republish government press releases, it’s hard to feel that you are getting the whole picture.

The Internet allows one to easily look outside our borders and read international news. And that news is different. That shouldn’t happen. Yet it does.

I just added no. 6 based on Phil’s tweet and some other things I have been hearing.

Jay, I think you should consider moving #6 up the list. The image of David Gregory dancing with “Grand Master” Rove at the Correspondents Dinner is an icon of the insider image of the national media. (I’m sure a Democratic version can be found as well.) Add in multimillion dollar contracts a la sports figures, and the sports-like coverage of public policy and public figures, it’s no surprise that actual journalists have given way to infotainers who appear to shill and suck up to the powerful not hold them accountable.

Bob:

All coming to a head in Colbert’s WH Correspondents Dinner performance. He really said what everyone outside of Versailles was thinking re: the corporate media.

I’d like to make an additional point about confidence in the press. Confidence is a measure of audience perception, not a measure of the actual worthiness of this confidence label. Hypothetically, it could be that the press is doing a better job now overall than they did 40 years ago. That audiences (or the people formerly known as the audience) don’t trust the press as much could actually mean that audiences have become more savvy and thus, more aware of potential failures by the press than we used to be. Maybe the press is doing at least just as well, but audiences have become more critical. I remember reading a group interview from a few years ago, for instance, including people like Ben Bagdikian and David Halberstam (and other luminaries), where they were asked about the Glass and Blair plagiarism scandals. Across the board these great journalists suggested that plagiarism used to be a much greater problem in years past (when tit was more difficult for outside fact-checking and general surveillance of the press).

Mainstream Press is corporately owned. There’s a feeling that what gets covered is in the interests of the owners and not truly watchdog not a searching out of difficult or inconvenient truths but just playing part of the political game, to corporate advantage. Journos are stuck with editors who do what owners want, in this view. And there are also lazinesses built into any system… Journos become insiders as they cover a story, unless they’re very careful. And they aren’t, it seems, nor fierce enough.

Bias — but not in the way it’s typical envisioned.

There was a book out in 2002 called Tilt? The search for media bias and the fascinating thing it uncovered is that there is a bias toward coverage of biased media. In general, coverage itself wasn’t actually biased–and the researcher included a wide range of past studies.

The media talk about media bias, which continues the cycle of mistrust and keeps it on the public agenda.

This ties into journalists as professionals, because the training insists on being unbiased which would mean covering criticism of the press too. But what we end up with is a profession criticizing itself and pointing out its own weaknesses, creating a cycle that continues to break down trust.

Aren’t #1 and #5 almost the same thing? If journalism is professionalized and institutionalized, it’s not surprising that public attitudes about the press will behave similarly to public attitudes about other large and remote institutions.

If you were to expect anything else, it would be because you think of the press as something other than a large remote institution.

Phil Williams got at the most important angle, I believe, and I’d like to expand on it a bit. You say that the press is or should be a check on institutional power, therefore #1 is likely not right; but the press over this period has both become more institutional and become so more visibly. Ergo, it’s just another power structure to distrust.

Don’t forget that besides the increase in professionalism, in the 1970s and 1980s the ownership of most news organizations became not only more concentrated but more corporate. The great family-owned newspapers started to sell out to the big chains in large numbers (my hometown papers were bought out in 1973), and broadcasters were snapped up as ownership regulations became more lax. This all blurred the line between Big Business and the scrappy news hounds. Both the perception and the reality of the watchdog role have taken serious hits in the past 40 years.

I think your first reply, from Victoria, “Alternative media sources provide a richer and more varied perspective than mainstream media,” is more correct than she realized. But alternatives to the almighty news sources began long before the arrival of the Web.

Your chart shows a rise in trust of news from 1973-1976. 1971 was the year of the Pentagon papers, ’72 was Watergate and ’74 was the movie “All the Presidents Men,” the story of the news uncovering Watergate. So first off, the peak in 1976 is likely to be higher than an average of previous years. You don’t source the chart, and we don’t know, but I am going to guess that no one even bothered to measure ‘trust in news’ before ’73.

So, beginning from what we must call an artificial highpoint (Robert Redford in his prime!), trust was bound to fall, and by 1980 was back where it was in ’73.

But that’s when the real changes began. Starting in the ’80s, there was tremendous growth in the number of TV channels via cable. 1980 was the year that CNN launched, and 1985 when Fox created the “fourth network”. More news sources equaled less credibility for each. Concurrently, TV news came to be seen as a revenue source rather than the old “loss leader,” (who wouldn’t trust the news less when it became all about making money?) Newspapers soon followed suit.

At this very moment, the precursors to the Web, BBS and email, began to spread. Email chains were common in those days, and along with BBS, new interpretations of the “truth” by the nascent citizen journalists were flying all over the place.

So if you trace the history of the expansion of news sources against the fall in trust, I think you will find a direct correlation.

Excellent points, Evelyn.

But All the President’s Men, the movie, was 1976.

Thank you Jay, and I stand corrected. The book came out in 74, the movie in 76. An even better fit with your chart.

“More news sources equaled less credibility for each”

I agree that there each ended up with less credibility.

I disagree that this was necessary as if there was a limited amount of credibility to go around.

Each source earned credibility to the extent that it fulfilled its journalistic mission to help people make informed decisions.

To the extent that the source didn’t, it lost credibility.

I would argue it is straightforward to explain the endpoints of the long 1974 to 1998 drop. Watergate probably represented the historic high for this time series (too bad there are no data for before that time period). By 1998, we had the spectacle of the Clinton impeachment travesty. In the latter case, I’m surprised that the positive line is still hanging on over 50% at that point. The very linear trend between these two points makes me wonder how frequently data was gathered, but it is not a stretch to suggest that the transition between these two extremes was a continuous and smooth process. After 2000, the web can account for the decrease, since we can now quickly confirm for ourselves that the the emperor has no clothes.

And the minor bump up in 2002 is probably due to a post-9/11 rally around the flag phenomenon…

There’s no doubt. Which is ironic, because the press did some of its most pathetic work at that time.

A wise man once asked, “What becomes of the press when the public’s constitution alters or weakens?”

Here’s what the gentleman is referring to:

http://bit.ly/JhxtgY

p. 20 of my book, What Are Journalists For?

Lack of accountability. No matter how many big stories the journalistic herd gets wrong (the lead-up to the Iraq War comes to mind) the high-profile talking heads stay the same.

I considered adding that one to my list of five.

I think that’s true not only in the press but in institutions in general (and has contributed to growing distrust of institutions): Once you reach a certain level in society, you are no longer accountable. You can run a business into the ground, oversee a decades-long continuing criminal enterprise involving the sexual assault of children and obstruction of justice, allow a U.S. city to drown, order torture and other crimes against humanity (well, maybe YOU can) and NOTHING HAPPENS.

I agree.

It reminds me of Brian Williams being called our not only for relying on a pundit who just happened to be a retired general briefed by the Pentagon on how to sell the war in Iraq, but on blacking out David Barstow’s Pulitzer-winning expose of the scandal.

His response? “I know him personally. He is a friend. I trust him.”

And

When profitability becomes more important, accountability becomes less important.

And, when the news anchors are making 5 million a year, with whom do you think they identify? NOT the people they are supposed to be helping make informed decisions.

I do think the Left’s concern, seen in the comments, about the corporatization of the press and “Big Media builds mistrust” deserves a hearing. News organizations that became part of the political and economic power elite, acting as gatekeepers, may be part of the answer.

I would also recommend linking to PBS and Fallows on why the press is hated.

I would also recommend contrasting Fineman’s AMMP with the watchdog role that attacked other institutions.

Finally, I’ll offer a reading list of important publications on what’s wrong/causing the decline of the press.

How about just poor performance over a protracted period of time as an explanation? Closing bureaus, laying off journalists, relying on opinion rather than journalism, just making it all up, a la Jayson Blair et al… Trust is something that has to be earned–and can also be lost if unearned.

In any event, trust is the key issue before us all now — how can we find credible news and information we can rely on — the key topic in my new book should you care to check it out:

Friends, Followers and the Future: How Social Media are Changing Politics, Threatening Big Brands, and Killing Traditional Media

http://www.citylights.com/book/?GCOI=87286100981880

A combination of factors Im guessing but I’d add the exponential growth of media which has undermined its value. When information was sparse(r) you valued those who brought it to you. When you are surrounded by a cacophony of information, much unwanted, it’s an irritation. Plus the deliberate mixing of opinion and news – but we’ve been over that ground already!

Thanks, Richard.

Really well said, this: “When information was sparse(r) you valued those who brought it to you. When you are surrounded by a cacophony of information, much unwanted, it’s an irritation.”

Of course that would really apply after 2000 or so. There was a steep drop before then.

I’m not a historian or a person of color, but would that chart be the same for African Americans? I’m just wondering if their trust in the press was ever that high and what it looks like today. There must be polls that have ethnic and gender break-downs.

Except that the rot had set in before 2000. Part of it, I think, is that our flagship media had already begun to prove that we couldn’t trust their news judgment or their reporting. The Times‘s Whitewater and Wen Ho Lee reporting were creatures of the 1990s. The Judith Miller debacle was all of a piece with it, and tended to destroy any optimistic hope that things like the Whitewater coverage had been an aberration.

If something is of low intrinsic value, scarcity isn’t going to make it look all that much better. The dropoff may have more to do with the speed at which the public internalized the sense that what the press had been serving up was of low intrinsic value than with the end of scarcity.

“When information was sparse(r) you valued those who brought it to you. When you are surrounded by a cacophony of information, much unwanted, it’s an irritation.”

I disagree that it is a zero sum game. To the extent that a media source helps people to make informed decisions, it is trusted, not matter how many other media there are. To the extent that it doesn’t, it does not earn trust.

I have another factor which is inadequate as a full explanation: the proliferation of cable news channels and the race for ratings in network and cable news outlets. CNN debuted in 1980, which is right at the beginning of the chart. As the most “visible” news sources for many (most?) Americans, national TV news I think plays a big role in shaping the view of the press as a whole. So when they do something ridiculous, or artificially blow up coverage of an unimportant story, or simply fail to do all their homework before going live with something, the perception of the media as a whole suffers.

Not to mention the massive spread of what I’ll call “personality news” — that is journalists whose personalities (and the biases that accompany those personalities) are as much of the reason people watch as the news they’re charged with presenting. It’s become less important whether or not you trust the institution behind the news, it’s all about whether you trust (or simply like, or even have a crush on) the personality conveying it. And when those personalities are outrageous, and their ratings skyrocket, the other outlets try haphazardly to replicate the success with their own crazies.

I say all of this, of course, sitting cozy in my newspaper role. No room for blame here! Move along.

I’ll add one more factor: An entire industry has sprung up devoted to undermining public confidence in the nonpartisan press. It’s not only a conservative movement — liberal groups do it too. But since the Web dramatically reduced the startup cost to get your news product “to market,” it’s been in the interest of partisans on both sides to undermine the established institutions who serve that watchdog role, because they would rather the public get their news directly from them. This of course doesn’t account for the slide in confidence pre-Internet, but it’s been a growing contributor to distrust in the press in the last two decades.

@NickHeynen

Hi, Nick.

Your first comments about cable news and “personality” is what I was trying to get at with No. 2.

This… “An entire industry has sprung up devoted to undermining public confidence in the nonpartisan press” deserves some additional thought.

Thanks for helping me out.

Indeed: The sophistication of propagandists devoted to undermining fact-based thought keeps growing, and to undermine facts they must also undermine fact-based institutions. That would include reporting.

Jay, thanks for the provocative question and the useful frames. I think you are asking both “What happened?” but also “Did it have to go this way?” My first newspaper article was in 1974 — in Newsday — so I like to think that I was the one responsible for the decline.

When you combine your five causes, they constitute a powerful, I would say irresistible force of decline.

But it would also be interesting to test the influence of certain signature, polarizing culture events, such as the Supreme Court decision in January 1973 legalizing abortion.

How important was that event in setting the sides for the culture war that divides Americans to this day? It was the kind of issue that murdered neutrality, which, in turn, made the “disinterested” press harder for partisans to embrace.

Thanks for stopping by, Roy

Yes to… “What happened?” but also “Did it have to go this way?” Was it inevitable, like, say, the loss of the paid classifieds to the web? Or was it correctible if there had been more vision?

I agree that culture war is a huge factor here, and I may have to fashion that into no. 7 above…. But I would start the clock in 1968 with the birth of Nixon’s southern strategy and 1969 with Agnew first attacks on “these men of the media.”

http://faculty.smu.edu/dsimon/Change-Agnew.html

Into that rising climate of rancor came Roe v Wade.

I wish there were data points from the 60s and between the 70s and 90s. Too much room for this kind of ideological speculation of the political/culture war impact on trust in media w/o them. I have seen little evidence correlating Nixon/Agnew to this poll.

For example: “The General Social Survey, a massive national poll conducted by the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago, has been measuring public confidence in institutions for more than three decades. From the 1970’s through the mid- 1980’s, confidence in the press was as high as it was for other major institutions— the military, Congress, religion and education, to name a few. But in the late 1980’s, ratings for the press began to slip, and by the 1990’s the slip had become a slide. In 1990, 74 percent of Americans said they had a great deal or some confidence in the press. A decade later, that number had fallen to 58 percent. During the same period, confidence in other institutions remained stable”

This 2009 Pew report also provides important data that breaks down “the media” into specific news orgs and differences in ideological demographics.

I disagree that, for instance, Roe v. Wsde caused the polarization. As with most divisive issues, it was taken advantage of by those wanting to divide the populace.

I looked for the report I read that showed the time lapse between events like Roe v. Wade and the DECISION to politicize them for electoral gain, but I couldn’t locate it. Sorry.

Great discussion! But I’m stunned nobody has used the word “class.” As journalists professionalize, they (seek to) step up in class. Readers are left behind. When you add the widening class divisions of the last 40 years — not just in income, but ways of looking at the world — you get mistrust.

I didn’t use the word “class” but I did use the concept:

“Journalism was becoming less of a trade and more of a profession…”

This is excellent Jay. I’ve been writing about this for many years, because I started in “the biz” in 1970, so it happened on my watch. My view is that Watergate itself, that pinnacle of “journalistic achievement” altered the professional industry forever by elevating the status of journalists to celebrity. After that, young people viewed the industry differently, while the people formerly known as the audience shook their collective heads. Market hopping became the norm. Young people interviewing for jobs often mentioned Watergate and had that sparkle of “me too” in their eyes. Moreover, I’m not convinced that people viewed Watergate with the same eyes as those who wrote the first draft of its history. Then there’s the movie starring, of all people, Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman. The glamour of such power, oh my.

Chris Lasch wrote in “The Lost Art of Political Argument” that the decline in participation in the U.S. political process could be directly tied to the rise in the professionalization of the press, and that, too, plays a role here. I think this is a big part of what’s unraveling before us today, and I, for one, welcome it.

A few years ago, I was making a presentation at CNN when someone asked, “But what about our credibility?” I pointed to the image you used above and responded, “What credibility?” Most people in traditional media think that blogs disrupted trust, but as you’ve pointed out, blogs are a response to the lack of trust in the press, not a cause.

Keep the faith.

I wonder how the Watergate myth played out in the pedagogy and curriculum that accompanied the rising number of journalism students.

Those are valuable observations, Terry, especially this one:

“Market hopping became the norm. Young people interviewing for jobs often mentioned Watergate and had that sparkle of ‘me too’ in their eyes.”

It reminds of the time I was sitting in a meeting with Knight-Ridder editors in the mid-90s. They were trying to understand why their newspapers felt so disconnected from their communities. I asked them, “Well, do you pay your reporters enough to own a home in the town they’re reporting for?”

Everyone looked at his or her shoes. Mostly his.

I agree with Terry here, and to take the market hopping theory a bit further–career hopping. It is a bit more recent, and may hardly account for the precipitous drop in the 80s and 90s, but may account for continued losses.

Public Relations has blossomed, offering new homes for the journalists that feel underpaid. Often in smaller markets, instead of hopping from town to town, many journalists are jumping ship for the greener pastures.

In that sense, we’re failing to develop experienced and savvy journalists over the long-term. In addition, television has become such a powerful medium. The addition of high definition has increased the value of “looking” the part vs actually “acting” the part. I’ve seen where a stronger journalist is passed over for a better looking television personality.

I too see Watergate as a watershed. Before Watergate, most people entered journalism to be writers, and newspapers were filled with story-telling.

After Watergate, the fulcrum shifted, and most entrants wanted to be reporter-heroes. For several reasons, this coincided with the rise of professionalism, with its expert-speak and policy focus. As these trends intertwined, storytelling waned, and reader interest — and trust — waned with it.

Rosen —

Given your repeated, and justified, insistence, lo! these many years, against the conflation of the term “press” with that of “mass media,” it is extraordinary that a decline in confidence in the mass media as a news-delivery system should inspire you to ponder about the reputation of journalism. Talk about category error.

I side with the comments of Victoria, Evelyn and Sambrook in this thread: the phenomenon being observed in Gallup’s trendline is the fragmentation of mass media. Journalism’s reputation may — or may not — have declined during this period, but that is not what Gallup is measuring.

Consider this chart of the audience for the broadcast networks’ nightly newscasts — as good an index of mass media journalism as one could hope for — and you will see a steady defection since 1980 that correlates excellently with Gallup’s data.

Gallup’s question concerns newspapers, TV and radio as delivery systems for journalism and it asks about comprehensiveness, accuracy and fairness. Two quick points:

Commercial radio started its switch from mainstream journalism to the talk format long before the Fairness Doctrine was officially repealed, so that third of the newspaper-TV-radio troika disqualified itself as a reliable news delivery system quite early in Gallup’s trend, long before the World Wide Web arrived.

Of the three attributes — “fully, accurately and fairly” — there is no one under the sun who would claim that the mission of “mass media” journalism is, or should be, to be granted a great deal of “trust and confidence” in delivering the fullness of a news story. Mass media organs exist to deliver headline news on the basic level to a general audience; for detail and comprehensiveness one consults to niche sites.

The Gallup chart may be very misleading. There are NO data points for the drop between the last survey in the 70s and the next survey in the 90s. There really should be no line at all for the 15-20 year period when the question wasn’t asked.

Not correct. Terry Heaton of AR&D research made the chart, and I asked him if I could run it. I put this to him and he sent me the data from Gallup: The first column is “great deal+fair amount.” The second is “not much/none”

1973: 70 30

1976 73 27

1979 71 29

1982 68 32

1985 65 35

1988 62 38

1991 59 41

1994 56 44

1997 53 46

2000 51 49

2003 54 46

2006 50 49

2009 43 56

2012 44 55

That’s a pretty clear pattern downward. There is only one blip: 2003, which is clearly the result of the nation being on a war footing.

Terry is looking for a link to this data.

What you are likely to find is Terry used data from a different question than the one on the graph. Since I have backed up my statement with a link, I’ll wait for your (or Terry’s) link to the data.

I first became aware of this about 10 years ago via Gallup. It appears, however, after looking through old links, that Tim is right. Gallup resurrected the question in 1997 after last asking it in 1976. Therefore, the 20 year line between those two days is implied. The spreadsheet I built to include later years were taken from the original Gallup image here, among other reports. I think this one explains it best (and includes numbers going back to 1968). I’m not sure the gap means much, but I do appreciate Tim setting the record straight. My bad.

Terry, thanks! I have linked to charts from the General Social Survey in the April 18, 2012 at 5:08 pm comment below that you might find useful.

Okay, then we–Terry and I–stand corrected.

My “incorrect” was incorrect.

Thanks Jay!

Tim, thanks for the GSS links. They tell the same story.

Terry, I think the data points from 80-83 and again from 90-93 tell a story that would be missed by interpolating across Gallup’s missing years.

My guess has been higher level of education in the populace combined with greater transparency of errors in news reporting and how news is gathered and reported. Educated people feel more confident in passing judgment, and the jump in education after WWII may have reached some critical level in the seventies. Personally, I judge a news source by how well they do on a subject or region I know something of – The Economist gained my trust through that. I assume if they report accurately on an area I am educated enough to judge, and add to my knowledge of that area, they will report accurately in other areas as well.

Was there more reporting rivalry between news sources in the seventies? As opposed to news baron rivalries which I know always existed, but news sources pointing out errors made in other news sources? The Internet did that for the past decade, so perhaps this happened in other forms since the seventies.

Out of your choices, my guesses are 1, 2, 5 (specifically the claim to provide all the news) and partially 6.

Keep up your public display of your work. This out-of-journalism reader has gained much from it.

“Greater transparency of errors in news reporting…” That is an interesting one. Consider: the error rate could be going down, but if the transparency of errors to the users is increasing, trust could decline despite marginally better performance or rising professional standards.

I think Yossi’s point is important but both you and he are looking at it backwards. If trust is falling because the audience knows more, is not the crux of the matter that the previous trust was unearned (see also: Catholic Church)?

Step one: be trustworthy. Step two: be trusted. Why are you skipping to step two?

Well said Sam.

I, for one, have expressed my disappointment with what passes for journalism over at NPR by writing comments to reports and to the ombudsman hundreds of times.

Not once has any of their “journalists” [sic] or “ombudsmen” [sic] seen fit to own up to anything or even admit there is room for improvement. Most recently, the ombudsman has fought to NOT disclose when the subject of a report is a corporate sponsor (!)

First, this is an excellent question. Now, immediately what comes to mind in trying to answer it is a mixture of the first possibility given (rise of mistrust in institutions) and the loss of innocence touched upon along the rationalization. There seems to have been, along with the rise of prestige of the trade, a shift of its conception as perceived by the general population. Journalism began to no longer be seen as a profession focused on delivering facts, but as a trade of delivering: 1- Spins, and 2- Marketing. This fits, further, with two interconnected historical developments: The explosion in population numbers and the proportionate explosion in mass communications. What fatally occurs is that each segment of the public has a news channel trusted, albeit the increase of critical thinking – a spin on educational success – also increases the rise of skepticism as to the sources’s intentions. Summing it up, loss of innocence, mistrust of public institutions plus dramatic increase in population vis a vis ideologies vis a vis mass communications vis a vis rise in critical thinking equal a very confusing environment to trust altogether. This with no mention to other symptoms of population explosions, such as apathy, or the development of information tech, creating a hyper information environment even harder and more confusing to keep track…

You had it at #4. Whether it’s parenting or the ER, “the wheel that squeaks the loudest gets the grease”. Most of the rest of these factors derive from or are caused by this controlling dynamic. Calling the press on liberal bias is just another way to be “cry out loud”. Joe Reader doesn’t want to complain about lack of professionalism except as this same cudgel.

Any other shortcoming that I see is that, except when engaged in longform journalism, the press seems too foten at loose ends. A seemingly valuable cohesion disappears or is too diffuse. Even though great individual writing overrides all the rest of this, the rise of revolutionary news gathering technologies does tend to devalue the quality of the prose.

Do we need to put some ideas on the table that can account for the short periods of increasing trust, or do we have all the ones we need already? (This is hodgier-podgier than what I’m used to seeing from Pressthink.)

The listed factors can be classified. I’d go with: General Issues (1), Meta-News (3,4), and News Mechanics (2,5,6).

I’ve looked over the comments so far with the goal of distilling and classifying. (By that I mean seizing on details, radically reinterpreting and filtering in hopes of boosting signal/noise ratio. Hope nobody’s married to their comments.)

General Issues:

* Responding to market forces

increasing investment, competition, profit-drive (Evelyn)

proliferation of the press – anti-institutionalizing (Victoria)

reinvention of the press – institutionalizing (Brian B.)

capture of the press – corporatizing (Naomi D.)

downsizing / talent drain (Rory O.)

* Weakening public (Gnarlytrombone)

Meta-News:

* Watching the watchdog (Christopher K.)

* Alienation of press from audience (Matt A.)

* Bias analysis cycle (Jenny F.)

* Blended news (Richard S.)

* Reversal of relationship to the executive (Bill L)

News Mechanics:

* Professionalization (Katie)

* Non-accountability (Doug M.)

* Gatekeeping (Tim)

* Personality Cults (Nick H.)

I’m not sure my attempted categories are holding up very well, but I do think Professionalization and Non-accountability go hand-in-hand, as part of the corporatizing process.

Most of this is prefigured in the Edward R. Murrow story.

Helpful. Thanks for the classification scheme.

I would posit that there’s also been a change in the last decade in the nature of what it means to be informed. The Internet made it easy for anyone to look up anything and do some of the kind of work journalists were once entrusted with. So people can pick and choose from a plethora of information sources and stick to what appeals most to them while distrusting everyone else.

In the days when people relied on area newspapers for information and read most of the newspaper each day in the morning, the plus side was they might get exposed to viewpoints they wouldn’t normally consider because their options were limited. The downside was their options were limited, so readers had to invest more trust as a matter of practicality. We live in an age of more autonomy, but that autonomy robs us of some involuntary exposure.

Numbers 1 and 6 are important factors.

However, I think the decline in trust also reflects the increasing polarization of society. A substantial portion of those who say they don’t trust the press answer that way because the press reports something–whether it’s on U.S. politics or the Middle East– that doesn’t fit with their ideology or worldview. They will never “trust” the press unless it’s a mouthpiece for their point of view.

News organizations try to address this by dutifully reporting “both sides of the story.” But too often journalists become merely stenographers who seem unable to use their insight, presence and knowledge to uncover and report what is really true. Instead, as Jay has said, they adopt the “view from nowhere” and fall into the trap of false equivalence. When this happens, news consumers who are looking for truth have every reason not to trust the press.

Given this, I’m surprised the trust number is as high as 44 percent.

Thanks, Dean. (Dean is the former ethics and standards editor at Thomson Reuters, and former vice president and editor-in-chief of MSNBC.com.) I want to point something out about the polarization you mentioned and its interaction with no.5. And yes, I am going to over-simplify and stylize the argument.

Let’s say 20 percent of the users won’t trust the press unless it’s a mouthpiece for their ideology. In the U.S. with two major ideological blocks that’s 40 percent of the users. If the standard response is to report both sides and assume the truth lies somewhere in the middle, then in that universe the user satisfaction index (USI) would be justifiably zero.

Meaning: The 20 percent on this side aren’t getting the ideological confirmation they want, the 20 percent on the other side aren’t getting the confirmation they want, and the 60 percent who want the news to help them get their bearings or know whom to trust aren’t getting served well, either. You wind up with a situation where everyone thinks they are getting screwed, including the journalists who get attacked no matter what they do.

I wouldn’t call it a “cause,” but it can’t be good for public confidence.

I liken this to some of the polling on the Affordable Care Act back when it was still in Congress: It had fairly high unfavorables, but when you drilled down, a lot of the unfavorables turned out to be from people who thought it didn’t go far enough — they weren’t all from people who flatly opposed the concept.

And given the wide gap that has arisen between the respective accepted sets of facts of Left and Right in this country, that’s a huge confidence obstacle to overcome even before you factor in any other possible reasons.

Could it be explained by the possibility that people overgeneralize when they talk about “the press” and “the media”? Could it be that the average person ascribes to all parts of the news media the faults of the one part of the media that offend them the most?

That basic idea is what I was trying to express in no. 2.

I tried articulating a few thoughts on these on Twitter earlier this morning, and I’ll try to pull them together into something coherent here.

When I think about this problem, I keep stumbling across a basic conundrum: When I think about this systematically – that is, when I apply the sociological principle that our relationships with social institutions (like the press) are dictated primarily by those institutions and the social structures around them, not by our individual attitudes – I come up with #1 and #5 (and #6, which is closely related to both) as the main explanations – by increasingly institutionalizing itself, the press has aligned itself with other social institutions in whom trust is declining while also adopting forms such as the View from Nowhere and “priesthood” mentality, all of which distance itself from the public from which it’s hoping to draw legitimacy.

But at the same time, whenever I ask my (non-academic) friends about why they’re frustrated with the news media, they always answer with #2 or #3 – the media’s all biased, they focus on sensationalism and celebrities instead of the facts, they just shout at each other and cheapen political discourse, etc.

So, maybe these two perspectives are examining the same basic problem on different levels. When the processes of #1/#5/#6 occur, they’re so gradual, deep, and structural – so “baked in” – that the average individual media consumer doesn’t see them and wouldn’t know how to recognize them even if they did. But those processes are what produce #2/#3/#4, which are the tangible outgrowths of a press driven by devotion to power, concern for self-legitimation, and the demands of being inextricably tied to a capitalist system.

So the real “root” cause is the institutionalization of the press in #1/#5/#6, but the way we see it is the content in #2/#3/#4. But the complaints the press receives about its performance are overwhelmingly along those content-based lines, so that’s what it responds to. This, as Jay noted on Twitter this morning, only makes the structural problem of #1/#5/#6 worse, because it’s trying to apply a superficial, content-based solution to a much deeper problem (that it won’t even acknowledge in the first place!). In a sense, their way of applying that “solution” is to double down on institutionalization, by trying to provide institutional solutions to a problem of which institutionalization itself is the root cause.

Excellent, Mark. Really helpful.

Now (excuse the school teacher’s tone) … How would you apply what you just wrote to this incident?

https://pressthink.org/2012/01/so-whaddaya-think-should-we-put-truthtelling-back-up-there-at-number-one/

I think that in that incident, you saw a rare instance in which the institutional enervation (or, to use your word, devastation) of the press was revealed in such startlingly naked terms that its public saw straight through the content/bias-based level of concern to the structural/institutional flaws of the press.

Yet even here, Brisbane didn’t recognize that the problem was on this institutional level. As he saw it, he was just responding to potential concern over an approach to content – should the Times break from its stance of strict objectivity in order to call out demonstrable falsehoods? To him, it wasn’t the window into the systemic failings of the press that it was to his readers; it was simply an everyday, practical question of how to properly practice objective journalism.

That blitheness indicates just how deep the willful ignorance runs in the press regarding its own systemic deficiencies – far, far deeper than its audience’s ignorance. Here, too, Brisbane is looking for an institutional solution (proper objectivity) to a problem created by institutional forces (truthtelling moving down the list of newsroom priorities). It’s laughably useless and head-in-the-sand, and the public knows it.

Great answer. Thanks again, Mark.

Mark – this is an excellent synthesis. Thank you. However, I think that we are not giving enough attention to the corruption that comes from monopoly rents. :-/

Something has been gained and something lost in the democratization of the media brought on my cable TV, first, and then the Web. The increase in voices has certainly broadened the discussion and given access to those often excluded by the gatekeepers, but it has also made the media seem like a Tower of Babel. It is now so hard to discern who is doing what — trying to tell the truth, give good analysis, spin, convince, cover up, confuse, whatever — that many simply say, “A pox on all their houses.” The good get tarnished by the bad, and by the mediocre. And it is much easier to ignore “the media” and simply say, “I believe what I believe.” As someone who grew up in the South, I can say the the very controlled establishment media shone strong lights on the state of race relations there (if not in the North) that were hard to ignore. Today, they would be ignored by many who would simply find their own outlets, websites, whatever that agree with their positions. Then they would tell pollsters that they don’t trust “the media.”

My sense is that not believing the news media has become an easy excuse. It’s part of our popular culture to distrust the media for a host of reasons — be it bias or errors or whatever. But detractors I come across aren’t great consumers of any type of news media. They distrust something they’ve rarely read or watched or heard. Perhaps it’s some sort of self-justification for not really paying attention to news. People aren’t informed and perhaps feel they need to make an excuse. So they blame journalism, saying in effect that even if they made the effort they wouldn’t be informed anyway. And don’t say that journalists have trivialized the news and made it harder than ever to become truly informed. With the abundance of news outlets using multiple ways to try to reach audiences, it’s never been easier to stay informed.

In a word, hubris.

Armed with the educations Yossi mentioned people came to believe they knew what was happening better than anyone else–without really doing the reporting. Along came the Internet, which gave them the tools to print what they think they knew, and (somewhat similar to the home improvement do-it-yourself boom that came with the introduction of Home Depot)you had…and still have… people publishing all over the place. I hear them now chanting “information wants to be free” (a phrase taken totally out of context…but then, who would know that if they didn’t go back to the source to check it).

Meanwhile journalists, also guilty of a similar hubris thanks the rise in their education and status, stopped listening to the public (because what did they know anyway?), which gave readers reason to want to grab control and say what they were sure they knew.

Now we’re in a situation where the public is sure you can’t believe anyone and readers are forced to be reporters whether they want to be or not, checking multiple sources to find out what’s valid…or perhaps not checking and so joining those who think what’s broadcast on Fox news (or other such sources)is actually true. But those people who believe in bad sources are not stupid necessarily. They are just looking for someone who represents what they see as the truth.

The solution to all this, I think, is going to be crowdsourcing…as well as exhaustion. Journalists now are looking to readers to provide information and insight that will set their stories apart. They are learning how to validate new sources to ensure they’ve got the story right. They are getting back to balance, but also to seeing what is real and valid for their readers. On the exhaustion side…it’s like Home Depot. Once people realized that all those pretty house parts required lots of work to put in place, they moved back to hiring builders to do it for them… at least most people did.

Of course, the neighborhoods will never look the same, but that is not all bad because in the end, having a little competition is what keeps us all honest…even if that competition does come from amateurs.

While all the reasons mentioned are valid, the most important really is that the business of journalism has eroded the profession. The profession emphasizes the craft–facts, disseminating information, a public marketplace for ideas. The business is sales, ratings, and market share. More of the effort these days in on manipulating the news, rather than reporting it. As my wife says, “you gossip for a living.”

This is a great list of comments.

I would point out that the graph is about “mass media,” and your question is about journalism. For the sake of discussion, I’ll assume that people asked that question are thinking about CBS News rather than Inside Edition or the New York Times rather than the National Inquirer. Also, given that fewer people are reading newspapers and watching TV, wouldn’t you expect the numbers to drop, especially as “online news” isn’t listed as an example of mass media in the poll question?

OK, enough of that. I add two things…well, I don’t know if they are additions because I haven’t read ALL of the comments.

1. During the period you mention, journalists became less “of the community.” They wrote stories — still do — that don’t reflect community interests or values. Because we’re so damned objective, we’re unable to communicate clearly that we are part of the people we’re writing for. Our story selection is antiseptic and doesn’t mirror what people actually care about or talk about. We charge for obits! For weddings!

(While I wish the lack of watch dog journalism was a significant cause, I can’t fathom that it is. I actually think that watch dog journalism erodes trust among a fair percentage of people. Example: I think a lot of people believe the L.A. Times should NOT have published the Zucchino story this morning on the grounds that it undermines U.S. efforts in Afghanistan.)

2. Our customer service is terrible. We eliminate content because we can, even though customers tell us they want it. They ask us for coverage and we don’t give it to them and we won’t explain why. (Or worse, we tell them that the thing they want us to write about isn’t important! Think how that makes a person feel.) We can’t get the paper there when we say we will. We don’t answer the phone and we don’t return calls. When someone doesn’t get their paper and go to the trouble to call to tell us they want one, we don’t bring them one. We credit their account. (It says that we don’t even think it is worth redelivering.)

I know that customer service isn’t Journalism with a capital J. But be careful not to dismiss it. When I think of companies I don’t trust — cable, computers, service — it’s because customer service sucks.

The worse thing is that once the trust is gone, it’s gone.

Especially important: “Because we’re so damned objective, we’re unable to communicate clearly that we are part of the people we’re writing for.”

Which is why I entitled my book, What Are Journalists For?

Thanks, John.

“1. During the period you mention, journalists became less “of the community.” They wrote stories — still do — that don’t reflect community interests or values.”

Agreed

“Because we’re so damned objective, we’re unable to communicate clearly that we are part of the people we’re writing for.”

Though it is not a journalists job to communicate that they are part of the community they are writing for, their work attains this objective simply by helping the community make informed decisions.

“Our story selection is antiseptic and doesn’t mirror what people actually care about or talk about. We charge for obits! For weddings!”

Agreed

“(While I wish the lack of watch dog journalism was a significant cause, I can’t fathom that it is.”

I couldn’t disagree more.

“I actually think that watch dog journalism erodes trust among a fair percentage of people. Example: I think a lot of people believe the L.A. Times should NOT have published the Zucchino story this morning on the grounds that it undermines U.S. efforts in Afghanistan.)”

I think you are confusing disagreement with trust. Telling the truth usually gains trust. I think it is emblematic of the state of journalism (sorry, but I assume you are part of the profession) that you would uncritically disseminate this justification for muzzling the press.

“2. Our customer service is terrible. We eliminate content because we can, even though customers tell us they want it. They ask us for coverage and we don’t give it to them and we won’t explain why. (Or worse, we tell them that the thing they want us to write about isn’t important! Think how that makes a person feel.) We can’t get the paper there when we say we will. We don’t answer the phone and we don’t return calls. When someone doesn’t get their paper and go to the trouble to call to tell us they want one, we don’t bring them one. We credit their account. (It says that we don’t even think it is worth redelivering.)

I know that customer service isn’t Journalism with a capital J. But be careful not to dismiss it. When I think of companies I don’t trust — cable, computers, service — it’s because customer service sucks.”

Agreed

“The worse thing is that once the trust is gone, it’s gone.”

I couldn’t disagree more. Trust can be earned, squandered and earned back. And it starts with individual journalists, outlets and then the industry. Just help people make informed decisions.

Just a hunch, but the early years of the fall of confidence are, I think, also the early years of the political focus group. So, the rise of a political methodology that the watchdog press isn’t trained to counter? See Michael J. Arlen in the February 18, 1980 New Yorker for a glimpse behind the curtain.

What a fascinating discourse. From the perspective of someone who went to work in newspapers in 1962, stepped away after a few decades to do magazines for a while, and now leads a Web journalism startup, I’d like to lob in two more causes for the decline in trust: