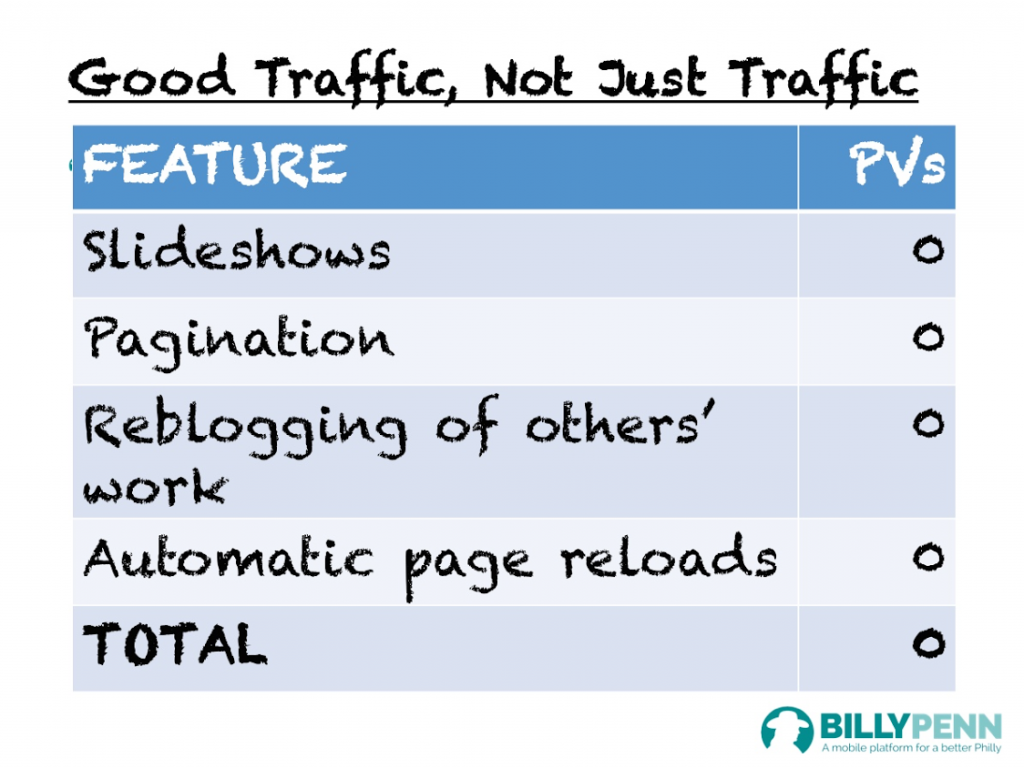

Last week Jim Brady, founder and funder of the Philadelphia mobile-first news start-up, Billy Penn, published a progress report 18 weeks after launch. “Our philosophy has been simple,” Brady wrote. “Think of the user first, and then worry about everything else.” To illustrate he included this chart:

Brady’s point in releasing a column of zeroes was to show that Billy Penn’s growth curve was modest but real. It had not been goosed by page view gimmicks, like dividing up a single article into multiple screens just to force some extra clicks.

There’s a bigger idea there, which I would call full stack credibility. Brady obviously believes there are benefits to operating a news site that not only publishes journalism you can trust, but extends trust production all the way through the start-up “stack.” Thus: monthly traffic figures you can trust. Or the kind of aggregation you can trust. (Dave Winer once captured it with his phrase, “People come back to sites that send them away.”)

Brady writes:

That’s not to say we’ll never do a relevant slideshow. But we won’t do them just for page views, since slideshows are often relatively valueless to a local advertiser. And we won’t paginate, because — let’s be honest — that’s never done for the reader. We won’t rewrite someone else’s story in order to hijack page views. The site that produces the original work deserves the traffic. Plus, every minute the Billy Penn staff spends “aggregating” someone else’s story is a minute we’re not producing our own.

That word “deserves” suggests a kind of moral philosophy at work, a theory of online justice. “Thou shall strive for a just distribution of traffic.” Link unto others as you would have them link unto you. You may have no other gods before the users. But if it were just about moralizing, full stack credibility would not be of much interest. Brady thinks there are business benefits:

We want to earn every page view, and focus on increasing that number by relentlessly serving our users. By doing that, we think we’ll create a better environment for advertisers and marketers, since they’ll have a better sense of our audience and more confidence their ads will be seen by the right consumer. In a sense, we’re pursuing a strategy that treasures “time well spent” over any other metric.

Not time spent, but well spent. It’s that little difference I am pointing to.

Definition: When you try to make not just the journalism, but every layer of the operation trust-worthy — not because you’re saints in start-up clothes but because you believe an editorial business operates better that way — that’s full stack credibility.

Now, almost 20 years of writing on the internet has taught me the necessity of adding something here: I’m not claiming there is anything “new” in this philosophy, or that it is original to Jim Brady or Billy Penn. I’m not saying Brady and Co. always live up to it, or that they can’t be caught in a contradiction. I’m sure they can be. I’m sure they will be. I’m not saying no one has written about this before, or given other, fitter names to it.

Look: in some ways it’s the oldest (and sappiest) chapter in the business evangelism book: serve customers, make a good product, practice thrift, show integrity in all your dealings… and you will prosper. If only it were so simple, right?

Credibility in editorial work is harder than it looks. That’s what I am saying. It’s not enough to produce stories that hold up to scrutiny. It’s not enough to nail the facts, or justify the headline. Those are vital. But there are other factors involved.

In a recent post at Nieman Lab, Celeste LeCompte, previously managing editor and director of product for Gigaom Research, notes what many others have noted about the sudden demise of that site: the editorial staff was blindsided.

Gigaom, like most private media companies, didn’t share much detail about its finances with employees. Editorial teams, in particular, are often left out of any open discussions on such matters. Few journalists that I’ve met know much about the state of their company’s finances, except maybe the freelance and travel budgets — and that’s about as far as the knowledge runs. This lack of financial transparency is pervasive throughout the industry — and it’s a problem that media companies would be wise to fix.

LeCompte doesn’t leave it at that. She tells the story of a small media company she worked for that adopted open-book accounting for its staff.

It was a revelation. Sure, as a business journalist, I was used to asking companies about their numbers, looking at earnings statements and SEC filings every now and then. But companies are usually doing whatever they can to put their best foot forward, even in their published numbers. A front-row seat on the finances of my own employer was a different matter entirely.

The transparency made me both a better reporter and a better employee. I could see more clearly the real costs of running the business: how the cashflow cycles worked, how the different business units were related, and what was working — and what wasn’t — for our own products. That enabled me to ask better questions about why decisions were made — and sometimes to understand why big changes needed to happen, even if I didn’t like them.

Full stack credibility says that what you tell your employees about the state of the business also has to be credible. That’s no homily. “Sometimes the most difficult challenges you have in the business are interdisciplinary ones,” LeCompte’s ex-boss told her. (He’s still sharing the finances with his staff.) “You need people in different parts of the business to work on it.” They can’t do that if they are kept in the dark, as Gigaom’s writers and editors were.

Writing about the same events, Danny Sullivan of Search Engine Land described a class of successful niche publications that have credible business models.

Over at The Information, Jessica Lessin’s kick-ass crew has been producing some of the most outstanding tech coverage you’ve ever seen. That’s not for a mass audience, since most of the masses aren’t going to shell-out $400 per year for it. But it doesn’t matter to Jessica, because as long as she’s got the audience she needs paying the bills and producing profits for her company to do great journalism, she’s good.

That’s part of full stack credibility too. The business makes transparent sense. Where the journalism plugs into the model is clear. The case for quality is compelling. The scale is livable and smart. In the whole contraption one can trust.

Our reporting is truthful but our page view metrics lie: that does not compute. (Many sites have this problem.) We want transparency from the companies we cover but we leave our employees in the dark: sign of a weak business. (Gigaom showed us that.)  You can rely on us for hard information but we make it hard to reach us if you have information: not credible. (Reuters has this problem.) We’re fast to post but slow to correct: no good no matter who you are.

You can rely on us for hard information but we make it hard to reach us if you have information: not credible. (Reuters has this problem.) We’re fast to post but slow to correct: no good no matter who you are.

I know what you’re thinking: where is the limit? Must there be total transparency about everything or nothing works? Do you have to give away all your secrets, let employees know about every setback suffered or dime spent? Must you really be holier than your industry’s thou? This is not what I’m saying, though I realize I am risking that read. I’m just not a good enough writer to avoid it!

Last try: It’s not “are you credible?” It’s: how many layers are you credible at? Full stack credibility is a philosophy that says: we may need all of them for any of them to work well. Sure, it’s a demanding standard, but that doesn’t mean it’s impractical. It may be the best way to build a news company that lasts.

2 Comments

For some reason, the Internet has not warmed to the idea that all clicks aren’t equal, which is standard in plenty of other contexts — obviously, all TV viewers are not equal.

Other than keeping employees informed about how the business is doing and how the various departments work, what’s new?

If it were easy, everybody would do it. Since not everybody is doing it, it must not be easy.

Why not? And how is this new effort going to do it anyway?