First, let’s summarize the criticisms: These are the complaints journalists talk the most about. Not the only complaints that have been made — or the most apt — but the ones they tend to listen and respond to.

Campbell Brown, formerly of CNN, writing in Politico:

“I believe Trump’s candidacy is largely a creation of a TV media that wants him, or needs him, to be the central character in this year’s political drama. And it’s not just the network and cable executives driving it. The TV anchors and senior executives who don’t deliver are mercilessly ousted. The ones who do deliver are lavishly rewarded… It is not just the wall-to-wall coverage of Trump. It’s the openness with which some are reveling in his attention. It’s the effort, conscious or not, to domesticate and pretty him up, to make him appear less offensive than he really is, and to practice a false objectivity or equivalence in the coverage. Here, journalism across all platforms—corporate, as well as publicly funded—is guilty.”

Jeff Spross, The Week.

“The basic charge — leveled by plenty of people — is that the media lavished massively disproportionate coverage on Trump because he generates clicks, and this ‘free publicity’ helped fuel his rise. But I’m not buying it.” (See especially: $2 Billion Worth of Free Media for Donald Trump.)

Dean Baquet, New York Times:

“The backdrop of the debate is that it’s the press’ fault that Donald Trump has the Republican nomination and that it’s the press’ fault that Donald Trump is running neck and neck with Hillary Clinton. I don’t buy that for a minute.”

Chris Cillizza, Washington Post:

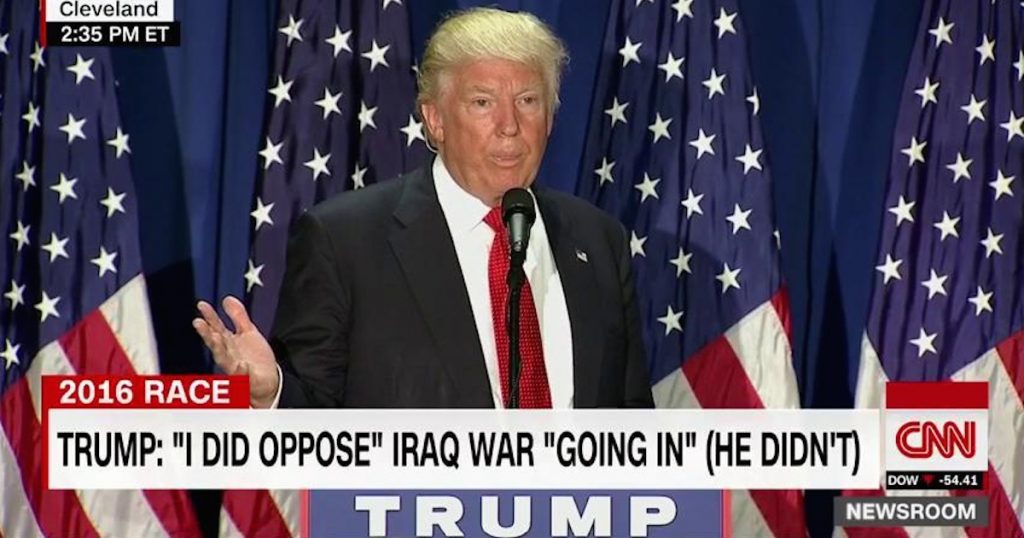

“[There’s a belief that] the media has failed in its responsibility to hold Trump accountable for the many and various misstatements and outright untruths he has peddled in this campaign. If the media was doing its job, the argument goes, then Trump would have never come so close to winning the Republican nomination, much less be within striking distance of Clinton at this late date.”

Rex Huppke, Chicago Tribune:

“Trump and his fervent followers refer to the media as scum and liars and traitors, and the candidate’s campaign routinely sends out fundraising emails that paint the election as a war with ‘the liberal media.’ Clinton supporters shout down any negative news about her — be it relating to her health, her private email server or her family’s charitable foundation — as unfair and a false equivalence, implying that anything bad that she has done is irrelevant because Trump has done bad things that are much worse.”

To the criticisms they are willing to hear journalists give these replies. I know because I listen to them talk about this a lot: on social media, on TV, in columns and blog posts, on panel discussions (I was at one this week with Molly Ball, Arianna Huffington and Marty Baron.) These are the responses I hear the most:

- Sorry, your beef is with the voters. The viewers. The clickers.

- Blame culture war. And partisan politics. And echo chambers.

- We’re not the gatekeepers. We don’t have that kind of power anymore.

- Yes, we gave him a lot of attention. Because his rise is an amazing story!

- Voters have a very jaundiced view of Trump. Because we did our job.

- Quit griping about “the media.” There really is no such thing.

- Hey, Trump earned a lot of it. Most accessible candidate ever!

- Stop whining about false balance. It’s not our job to win it for your side.

- What bothers you is that all the negative coverage he’s gotten isn’t working.

- Trump won massive mind share because he’s an innovator— and a media genius.

In a minute I will explain each one, with quotes to show you what I mean. But first I need to clarify two things about this post.

I am not trying to evaluate these responses from journalists. Rather, I am trying to be descriptive. I’m not saying I “buy” their replies. I’m not dumping on them, either. I’m trying to listen to The Criticized and tell you what they’re saying back. In other writings, I’ve been critical of election coverage. You can read some of it here and here, or check the “Recent Entries” section of my site. If you want to know what my politics are, go here.

Second clarification: I am not trying to capture what committed Trump supporters and people in the conservative movement say about the treatment of Trump’s candidacy by mainstream journalists. For the most part committed Trump supporters and people in the conservative movement have one thing to say: There is no journalism, there are no journalists. There is only politics — Democratic party politics — going on. In this view, the people who call themselves journalists are not trying to find out what’s happening and tell the voters. They are not struggling to hold the candidates accountable while holding on to their audiences. They are Democrats trying to win the election for their side. That’s why no one with any sense trusts them— again, according to this view.

“Democratic operatives with bylines” (coined by Glenn Reynolds) is the phrase that best captures this sense, which has become pervasive on the right. I hear that sentiment all the time from drive-bys on Twitter and in the comment section of my site. It is rocket fuel for the Trump candidacy, and bedrock for the Breitbart view of the world, in which “the media” and “the left” are interchangeable terms. I’m not dismissing the importance of this view; on the contrary, I think it is one of the most consequential developments in American politics in the last 50 years. But to take it seriously is to recognize just how completely the militant right has eclipsed journalism from its world view and media critique. There is no real reporting, just endless bias. There is no profession there with a code of conduct and a public service mission. Just politics: party agents with press cards. Because it is a fraudulent actor, “the media” must be defeated, discredited, and replaced.

The people who think this way don’t have much to say about how to cover a phenomenon like Trump and remain true to a demanding code of public service. They have one thing to tell the press: you’re trying to get Hillary elected. There are elements on the left committed to a “propaganda model” of news coverage who evacuate journalism in a similar way. That is worrisome. But they have nowhere near the same influence on the rank and file, and they have never captured a candidacy the way Breitbart has captured Trump.

I realize that many readers will hotly dispute the three paragraphs above. So be it. On, then, to my description of the responses from journalists to criticisms commonly made of their coverage of Trump.

1. Sorry, your beef is with the voters. The viewers. The clickers. The audience who responded to Trump, the public that wanted more and more of him, the crowds that showed up at his events in huge numbers, the people who pulled the lever for Trump in the primaries, the ones who are telling pollsters they will vote for him. Far more than journalists, they’re the ones responsible.

Eugene Robinson, Washington Post:

“Any carnival barker can draw a crowd. Trump would have been sent home to his Fifth Avenue penthouse long ago if a substantial part of the Republican Party base didn’t agree with what he is saying. If there is any sort of collective media failure, it’s in paying not too much attention to Trump but instead too little to his message… Blaming ourselves for Trump’s rise is just another way to ignore the voters who have made him the favorite for the GOP nomination.”

Molly Ball, The Atlantic:

“The press is the effect here, not the cause: The media were noting—often to their collective surprise—that more and more Republican primary voters were becoming receptive to Trump’s message. Should they instead have ignored or downplayed this development? Journalists shouldn’t blindly follow polls, but we should—constantly!—attempt to understand what sentiments are percolating in the electorate.”

Callum Borchers, Washington Post:

“News organizations enjoy the ratings and readership delivered by Donald Trump — just ask CBS boss Les Moonves — but they haven’t made him the Republican presidential front-runner. Voters who ignore or even embrace his venomous brand of politics and the many negative stories about him have done that.”

Matt Taibbi, Rolling Stone:

“An important news story or 10 will likely die on the vine while the country obsesses over Trump’s latest foot-in-mouth episode. That’s the paradox with this candidate. Even the people who wish he didn’t exist can’t take their eyes off him. No amount of ‘contextualizing’ or pointing out his flaws and deceptions can walk back his gravitational pull on audiences.”

Eric Levitz, New York magazine.

“The media lavished Trump with attention because the American people enjoy watching garbage fires burn. But only the GOP base wants to make a garbage fire our president. Thus, responsibility for Trump’s political fortunes rests with Republican voters — and the party that conditioned them to mistake flaming refuse for fearless leadership.”

2. Blame culture war. And partisan politics. And echo chambers. That phrase of Eric Levit’s, “the party that conditioned them to mistake flaming refuse for fearless leadership…” points to another reply I’ve heard journalists give when criticized for their coverage of Trump: culture war works.

Chris Cillizza, Washington Post:

“Trump’s ability to weather so many blatant falsehoods is far more complex than simply shouting at the media to ‘do its job!’ It’s about the increasing tribalism of our politics, the partisan siloing of our media and the result of years of committed efforts to discredit the neutral media referees.”

3. We’re not the gatekeepers. We don’t have that kind of power anymore. It has become more and more obvious to journalists in the mainstream press that politicians can go around them and voters’ information diet is not theirs to determine.

Michael Hirsch, Politico.

“It’s a critical moment for mainstream media that I think has been getting less and less relevant with each election season. We’ve seen recent presidents, starting at least with Clinton, trying to talk over the heads of the media, not always successfully. Trump has succeeded in talking over the heads of the media. And if he’s elected president, then that will underline just how irrelevant we’ve become.”

Ben Smith, Buzzfeed:

“The press mostly just doesn’t have the gatekeeping power it once had.”

Eugene Robinson, Washington Post:

“Commentators should spend less time flattering themselves that the news media have the power to make such a thing happen — and more time trying to understand why Trump is succeeding.”

Callum Borchers, Washington Post:

“It’s convenient to blame the media for Trump’s rise, but the reality — made dishearteningly apparent this week — is that the press isn’t powerful enough to be responsible for his success or failure. It can’t even control the campaign narrative, never mind the outcome.”

Jeff Zucker, CNN:

“I only wish that CNN had that much power to be able to create a frontrunner on either side… The critics of Donald Trump are looking for people to blame for his rise. There are many people who are either surprised by his strength, or don’t like him, and want to blame someone to explain why he has been this popular.”

4. Yes, we gave him a lot of attention. Because his rise is an amazing story! This was beyond “man bites dog.” This was “the laws of the political universe have been repealed.” Huge news.

Sam Reisman, Mediaite.

“Like it or not, a political neophyte coming down his brass-plated escalator from out of nowhere, violating every rule of political gravity, and wreaking havoc in one of our two major political parties — that is a major, ongoing story. But it’s his often frightening message to which we should credit his success, not the frequency with which it is broadcast.

Chris Cillizza, Washington Post:

“Beginning as a punchline — and an asterisk in polling — Trump beat the most crowded (and one of the deepest and most accomplished) Republican fields in modern presidential history.  A first-time candidate, he systematically dismantled Rick Perry, Scott Walker, Jeb Bush, Chris Christie and Marco Rubio — to name just a few. And, even amid the relentless media coverage of whether Trump had peaked or whether his moment had passed, he led the race virtually wire to wire. He won in the Midwest, the West, the South and the East. He won among very conservative voters and moderate voters. He won and won and won… It is, simply put, the single most amazing thing I have seen in my 18 years of covering politics.”

A first-time candidate, he systematically dismantled Rick Perry, Scott Walker, Jeb Bush, Chris Christie and Marco Rubio — to name just a few. And, even amid the relentless media coverage of whether Trump had peaked or whether his moment had passed, he led the race virtually wire to wire. He won in the Midwest, the West, the South and the East. He won among very conservative voters and moderate voters. He won and won and won… It is, simply put, the single most amazing thing I have seen in my 18 years of covering politics.”

5. Voters have a very jaundiced view of Trump. Because we did our job. Yes, we gave him a lot of attention, but a lot of it was negative. We questioned him, we aired his outrageous claims and fact-checked them, we investigated him, we showed Americans who he is. And it shows in the polls.

Brendan O’Connor, Gawker.

“Given how unfavorable Trump is viewed more broadly, isn’t it possible that widespread coverage of Trump—his insults, his misogyny, his racism, his scams, his bluster—has ensured that general election voters are… informed? Hmmm.”

Molly Ball, the Atlantic:

“So much has Trump ‘benefited’ from media exposure… that he now is viewed negatively by 70 percent of voters.”

Eric Levitz, New York Magazine:

“Recent polls show 70 percent of the American public now holds an unfavorable view of the Republican nominee, as he falls further behind Hillary Clinton in general-election trial heats. This dip was not the product of cable networks suddenly turning their cameras away from Trump. Rather, the media’s steadfast attention to the mogul’s various obscenities did what it has been doing for the past 12 months: increase the number of American voters that see Donald Trump as unfit for high office.”

Jack Shafer, Politico:

“No one but a dimwit would accept that all the Trump publicity—critical stories about his flip-flops and skeevy business deals; countless rebukes from fact-checkers; pieces knocking his views on eminent domain, his dubious modeling agency, his backstory as a birther and so on—helped his candidacy. There’s just as good an argument that all this coverage will end up hurting Trump: Should he claim the nomination, he will be the least popular candidate to start the general campaign in modern times, with a 67 percent unfavorable rating.”

6. Quit griping about “the media,” there really is no such thing. Isn’t it time we dropped this fiction? It’s not helping.

Brendan O’Connor, Gawker.

“There is no ‘we in the media.’ Within platforms or across them: What NBC News does has nothing to do with what CNN does, and even less to do with what the Times does.”

Paul Farhi, Washington Post:

“There are hundreds of broadcast and cable TV networks, a thousand or so local TV stations, a few thousand magazines and newspapers, several thousand radio stations and roughly a gazillion websites, blogs, newsletters and podcasts. There’s also Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram and who knows what new digital thing. All of these, collectively, now constitute the media. But this vast array of news and information sources — from the New York Times to Rubber and Plastics News — helps define what’s wrong with referring to ‘the media.’ With so many sources, one-size-fits-all reporting is impossible. Those who work in the media don’t gather in our huddle rooms each morning and light up the teleconference lines with plots to nettle and unsettle you. There is no media in the sense of a conspiracy to tilt perception.”

Paul Farhi, Washington Post:

“As I understand your use of this term, ‘the media’ is essentially shorthand for anything you read, saw or heard today that you disagreed with or didn’t like. At any given moment, ‘the media’ is biased against your candidate, your issue, your very way of life. But, you know, the media isn’t really doing that. Some article, some news report, some guy spouting off on a CNN panel or at CrankyCrackpot.com might be. But none of those things singularly are really the media.”

7. Hey, Trump earned a lot of it. Most accessible candidate ever! Maybe the other candidates should have put themselves on the line like that.

Frank Rich, New York Magazine:

“He gets a lion’s share of television time and other so-called ‘earned media’ because he earns it: Unlike Marco Rubio or Ted Cruz, he never limited his exposure to the press but seized virtually every invitation handed him to go on the air and mouth off unscripted.”

Doyle McManus, Los Angeles Times.

“At least he’s been accessible. He’s given far more time to interviewers – both broadcast and print – than Hillary Clinton, the presumptive Democratic nominee. Clinton’s last full-scale news conference was more than six months ago. Trump has held perhaps a dozen news conferences since then. According to USA Today, Clinton has appeared on Sunday morning interview shows 25 times since the campaign began; Trump has appeared 75 times during the same period.”

Eddie Scarry, Washington Examiner:

“On Tuesday, Trump made one of his many call-ins to the program for a 10-minute interview. At the end, co-host Mika Brzezinski addressed any critics who might be watching. ‘I should just point out, for all the eye rolling that I hear happening, that if Hillary Clinton, Marco Rubio or Ted Cruz would like to call into the show, we would take their call at any time,’ she said. Brzezinski said Trump ‘has proved himself to be the most accessible candidate, like it or not. But don’t blame us if the other candidates are not as accessible.'”

Howard Kurtz, Fox News:

“Trump has seized much of the ‘free’ air time by doing many, many more interviews than his rivals, and by driving the campaign dialogue—which all candidates try to do but are usually too cautious or dull to pull off.”

Jack Shafer, Politico:

“He’s disarmed the media by acknowledging that he’s a greedy man full of self-contradiction, and he has inspired voters with his positive and entertaining campaign. Trump also makes himself readily available to journalists for interviews, even when no camera is running. Remember, this is a man who got blanket publicity in 2007 when he announced he was going into the frozen meat business with Trump Steaks. Publicity ain’t free if you’re working for it! Maybe the other candidates should have worked as hard as Trump did.”

8. Stop whining about false balance. It’s not our job to win it for your side. And it’s not ‘false balance’ to hold both sides accountable, so we’re going to keep doing that. We’re not on the team. Quit asking us to be.

Liz Spayd, New York Times:

“I can’t help wondering about the ideological motives of those crying false balance, given that they are using the argument mostly in support of liberal causes and candidates.”

Molly Ball, The Atlantic:

“Journalists don’t write their stories to advance or hinder the candidacies of particular politicians.”

Matt Taibbi, Rolling Stone:

“The people complaining about ‘false balance’ usually seem confident in having discovered the truth of things for themselves, despite the media’s supposed incompetence. They’re quite sure of whom to vote for and why. Their complaints are really about the impact that ‘false balance’ coverage might have on other, lesser humans, with weaker minds than theirs.”

Glenn Greenwald, The Intercept:

“Aggressive investigative journalism against Trump is not enough for Democratic partisans whose voice is dominant in U.S. media discourse. They also want a cessation of any news coverage that reflects negatively on Hillary Clinton.”

9. What bothers you is that all the negative coverage he’s gotten isn’t working. It’s not that we have been insufficiently tough. It’s that people still support him because he’s “tapped into” (that’s a key phrase) something real. Deal with it.

Chris Cillizza, Washington Post:

“So, what is really going on here? What are Democrats trying to say when they continue to claim — facts be damned! — that the media isn’t doing its job fact-checking Trump? I think I know. What I believe people are saying is ‘Why doesn’t the fact that independent fact-checkers keep finding Trump lying not change people’s opinions of him?’ Or, put another way: How can someone who isn’t telling the truth two-thirds of the time possibly be in contention to be president of the United States?”

Dean Baquet, New York Times:

“I think that carries with it the belief that many people had that somehow if people really knew about his finances and all this other stuff, they couldn’t possibly vote for him. Guess what: They do know. There’s a tremendous amount known about this guy, and the press gets credit for that. I think Donald Trump has been investigated a whole lot by a lot of institutions, and I think it’s misunderstanding this moment, this moment in the history of the country and even in the history of media, to say he’s the front-runner because people don’t know a lot about him.”

Matt Taibbi, Rolling Stone:

“Anyone who tries to argue that there’s insufficiently vast documentation of Trump’s insanity is either being willfully obtuse or not paying real attention to the news. Just follow this latest birther faceplant. The outrage is all out there, in huge quantities. It’s just not having the predicted effect.”

10.Trump won massive mind share because he’s an innovator— and a media genius. Give the man his due. He created a new way to run for president.

Jack Shafer, Politico:

“Whether Trump wins or loses the nomination, he has done something new, creating an example that future candidates will be eager to follow. We can already envision these candidates, without organization, without advisers, without anything but a big running mouth. Existing outside the usual boundaries of what’s generally been allowed, the Trump style has three identifying markers: not exactly entertainment, but entertaining just the same. Not really populist, but popular. Not politics, but very political. Even people who can’t stand Trump have found themselves watching him and reading about him, breathing heavily until the next outrage. It’s his movie, and he’s the auteur.”

Robert Draper, New York Times:

“Trump was a TV star for more than a decade before he became a politician; he watches TV news incessantly and understands the medium intimately. He knows the optimal time slots on the morning shows. He stage-manages the on-set lighting. He is not only on speaking terms with every network chief executive but also knows their booking agents. He monitors the opinions of hosts and regular guests more avidly than most media critics do and works them obsessively, often directly.”

Bonus! There are some criticisms that journalists will sign on to. These are the ones I hear most frequently.

They didn’t take Trump seriously at first.

David Folkenflik, NPR: “For all of their obsession with horse-race coverage, much of the political press treated Trump’s campaign as pure spectacle, which it undoubtedly was, instead of something that could also draw support from real voters. As readers and viewers, we heard much more about what political insiders were telling us the voters thought than about the voters themselves.”

Hadas Gold, Politico: “From the most serious magazine journalists, writing with the voice of history, to most street-savvy, ear-to-the-ground bloggers: Trump had a polling ceiling; the Republican establishment would coalesce to bring him down; he didn’t have a sufficient ground game; one giant gaffe would inevitably bring him down; and on and on.”

Michael Hirsch, Politico: “We certainly, as I said, could have tried to do a better job challenging him, perhaps taking him seriously earlier rather than treating him as nothing more than a clown, and of course there was the spectacle of months and months going by where people in the media kept delivering judgments of ‘peak Trump,’ where we’ve now hit peak Trump and the inevitable decline will start, and it never happens, so just a massive misreading. If nothing else, you could say conclusively — and I think very few people in the media would disagree — that this was just a massive misreading of the political environment in this season.”

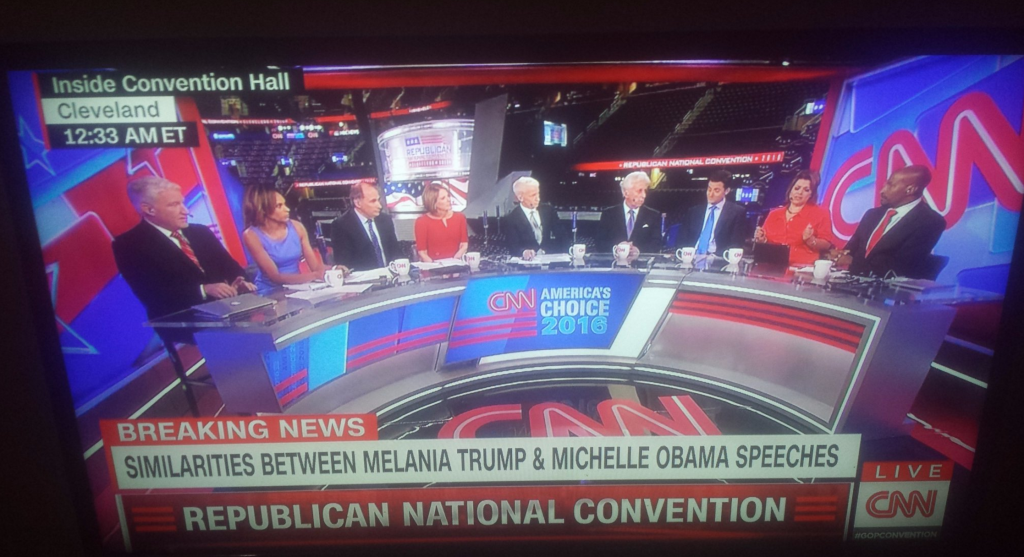

Maybe they did let Trump set the news agenda (and phone it in.)

Sabrina Siddiqui, The Guardian: “At what point do you need to say, ‘Okay, this is a fact, that he knows exactly how to dominate the news cycle. It’s a ploy.’ At what point do you need to say, ‘He is effectively calling the shots and managing exactly when he’s covered and how he’s covered’? And essentially — any day that Trump felt like he was losing traction, he would say something, and lo and behold, he dominated the day and the week again.

David Folkenflik, NPR: “Those favored by the great man were graced with sit-downs on camera. Others had to settle for Trump’s calls, always the least desirable option. Producers contorted themselves to accommodate him, accepting not just phone interviews but cellphone interviews. That held even for programs with major audiences such as NBC’s Today show and ABC’s This Week. At one point, BuzzFeed counted 69 televised phone interviews with Trump in 69 days. Media analysts of all stripes and ideologies assessed the coverage not just as disproportionate but wildly so. Even negative stories or controversies involving Trump pushed his rivals from news coverage.”

They developed a symbiosis or mutual dependence with Trump.

Jim Rutenberg, New York Times: “As the people have made clear, they want Trump. [Thus the] disturbing symbiosis between Mr. Trump and the news media. There is always a mutually beneficial relationship between candidates and news organizations during presidential years. But in my lifetime it’s never seemed so singularly focused on a single candidacy. And the financial stakes have never been so intertwined with the journalistic and political stakes.”

They had lost touch with Trump’s constituency

Dean Baquet, New York Times: “I do think we probably didn’t quite have a handle on how much the country was sort of torn apart by the financial crisis and other stuff, too. I think that I can make the case, if I’m being really reflective and self-critical, that there are parts of the country we probably were not quite in touch with. I want everybody to read the New York Times. I don’t think we understood that part of the country well enough. I think there was a bigger part of the country than we knew that’s really frustrated. I think we missed that story.”

David Brooks, New York Times: “Trump voters are a coalition of the dispossessed. They have suffered lost jobs, lost wages, lost dreams. The American system is not working for them, so naturally they are looking for something else. Moreover, many in the media, especially me, did not understand how they would express their alienation. We expected Trump to fizzle because we were not socially intermingled with his supporters and did not listen carefully enough. For me, it’s a lesson that I have to change the way I do my job if I’m going to report accurately on this country.”

* * *Photo credit:

Gage Skidmore.