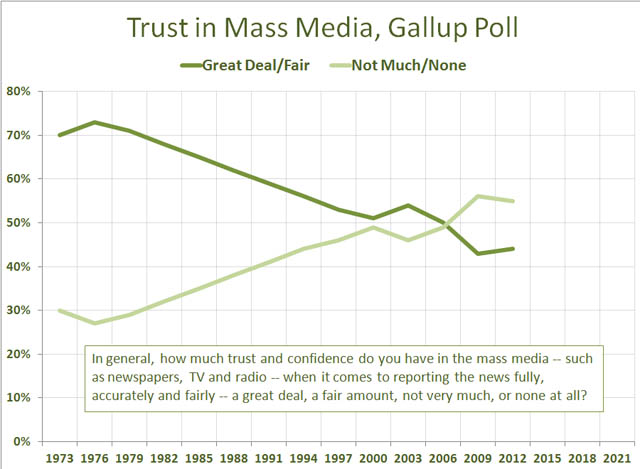

The percentage of Americans who had a “great deal” or a “fair amount” of trust in the news media has declined from over 70 percent shortly after Watergate to about 44 percent today.

Why? That is my question here.

It’s a puzzle because during that same period several other things were happening. Journalists were becoming better educated. They were more likely to go to journalism school, my institution. During this period, the cultural cachet of being a journalist was on the rise. Newsrooms were getting bigger, too: more boots on the ground to cover the news. Journalism was becoming less of a trade, more of a profession. Most people who study the press would say that the influence of professional standards, such as we find in this code, was rising.

So the puzzle is: how do these things fit together? More of a profession, more educated people going into journalism, a more desirable career, greater cultural standing (although never great pay) bigger staffs, more people to do the work … and the result of all that is less trust.

Why?

Let me be clear: I’m not saying there’s no explanation, or that this is some baffling paradox. Only that it’s worth thinking through how these things fit together. (For more on declining public confidence see this overview from 2005.) Here are some possible answers:

When you put the trust puzzler to professional journalists (and I have) they tend to give two replies:

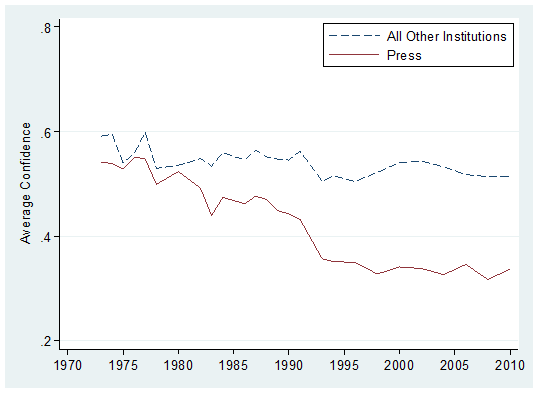

1. All institutions are less trusted. The press is just part of the trend. Here are a few comparison figures from Gallup’s confidence surveys (Pdf):

The Church. In 1973, 66 percent had a great deal or a fair amount of trust. 2010: 48 percent.

Banks. 1979: 60 percent, 2010: 23 percent.

Public schools. 1973: 58 percent, 2010: 34 percent

The Presidency: 1973: 52 percent, 2010: 36 percent

The problem with this answer is that it ignores the whole idea of a watchdog press. If these other institutions are screwing up, or becoming less responsive, then journalists should be the ones telling us about it, right? Suppose the Catholic Church fails (scandalously) to deal with child abusers among its priests. If journalists help expose that, confidence in the press should rise. That’s the watchdog concept in action. Big institutions are less trusted. But in itself that doesn’t explain falling confidence in the press. Public service journalism is supposed to be a check on those institutions.

2. Bad actors. The second answer I hear the most from journalists is that bad actors–especially the squabblers on cable television, and the tabloid media generally–are undermining confidence in the press as a whole. Just as Americans hate Congress but tend to love their local Congress person, they can’t stand “the media” — as reflected in your chart, Jay — but they feel differently about their own habitual sources of news. (Go here for some evidence of that.)

From this point of view, there’s no trust problem at all, really, just a category mistake. The most visible news people are being mistaken for the whole institution. If we could stop doing that, there wouldn’t be any drop in confidence.

The conservative movement has an answer to my question, which they try to drill into my head whenever they can:

3. Liberal bias. The United States is a conservative country (center-right, as radio host Hugh Hewitt likes to say) but most journalists are liberals. Even though they claim to practice neutrality, they weave their ideology into their reporting and people sense this bias. The result is mistrust. The problem has gotten worse since 1976. What else do you need to know?

Well, one thing I’d like to know is: how come Fox News, dedicated to eradicating liberal bias, is simultaneously the most mistrusted and the most trusted news source, according to survey research. That suggests it’s a little more complicated than: conservative country, liberal press. Wouldn’t it make more sense to begin like this? The United States is a divided country…

The political left has a different answer to my question. I should point out that it is not analogous to the right’s answer:

4. Working the refs. The right has learned how to manipulate journalists by never letting up on the “liberal bias” charge, no matter what. This amounts to working the refs, in Eric Alterman’s phrase. In basketball, some coaches will as a matter of course complain that the referees are favoring the other team. Their hope is to sow confusion in the minds of the officials, and perhaps get the benefit of the doubt on some calls.

Working the refs is indifferent to the actual distribution of judgment calls. Coaches who believe in the method use it regardless of whether the refs have been unfair (or generous) to their side. The aim is to intimidate. In the degree that “working the refs” works, journalists favor the side that is complaining the most. This amounts to a distortion of the picture presented to the public. From that distortion, mistrust follows.

But is it really true that the left does not know how to complain about bad calls, while the right screams at every opportunity? Maybe in 1969, when Spiro Agnew’s complaints began, that was so. It hasn’t been so for a while. This complicates the case.

My own theory, which I do not see as complete or even adequate.

5. Something went awry. My own sense is that the loss in confidence in the press has to do with professionalization itself. There was something missing or out of alignment in the ideas and ideals that mainstream journalism adopted when it began to think of itself as a profession starting in the 1920s. Whether it was newsroom objectivity, or the View from Nowhere, the production of innocence, the era of omniscience, the Voice of God, or the claim to provide “all the news,” whether it was the news tribe understood as a priesthood, monopoly status for metropolitan journalism, the identification with insiders, or an underlying media system that ran one way, in a one-to-many or broadcasting pattern… I don’t know. Maybe all those things.

I haven’t figured it out yet (in fact, much of my writing at PressThink has been an attempt to think this through…) but it strikes me that something went awry within the professional project–which also did a lot of good for journalism–and eventually that flaw began to take its toll on public confidence. The press got out of alignment with its public, and mistaken ideas that weren’t seen as mistaken prevented self-correction, resulting in symptoms like this.

The first addition based on a number of comments I received since this was posted.

6. Just part of the power structure now. Over Twitter, investigative journalist Phil Williams wrote, “Press more popular when viewed as standing up to power. Then it became part of power structure.” From this point of view, the glamorization of journalism after Watergate, combined with the influence of celebrity within the news tribe, plus the growing concentration of media ownership in a few large companies that themselves seek influence, had made mockery of the journalist as a courageous truthteller standing outside the halls of power.

Ground zero for this explanation would be the annual White House Correspondents Association dinner, in which all the factors I just mentioned are on vivid display.

I’ve been blogging at PressThink since 2003. The comment thread at this post may be the best since I started. Nos. 7-8 derive from it.

7. Culture war! Let’s say 20 percent of the country buys No. 3: liberal bias, 20 percent buys No. 4: working the refs, and 10 percent is ready to tear its hair out with the professional journalists’s imaginary solution: “he said, she said” reporting. (These, I think, are conservative estimates.) Put them together and half the country is angry at the press before it gets its boots on.

Like I said, America is a divided country. There’s a seductive pull to placing yourself in the middle between what you imagine to be “the extremes.” That seems like the safest position, but is it really? The trust figures suggest the answer is: no, not really. Have you heard CNN’s slogan for its 2012 election coverage? “The only side we’re on is yours.” But it’s just a slogan. CNN has no idea how to make it real.

8. Too big to tell. In the comments, John Paton, the CEO of Digital First Media, second largest newspaper company in the U.S. (Disclosure: I was for a time a paid advisor to this company) speculates:

Society has profoundly changed in the last three decades.

The factors are many: economics; wealth; job security and empowerment. Technology empowers but real power to change one’s life is perhaps even further outside of most people’s grasp than before – i.e. Job expectations; education expectations; home ownership expectations; upward mobility, etc.

If there is a growing awareness of those disconnects, then perhaps society understands that the news media has failed them on the bigger issues and no amount of exposing corrupt politicians and thieving captains of industry will let the news media regain that trust.

According to this interpretation, stories that are “too big to tell” (not that they literally could not be told but they overwhelm journalism as it stands today…) are the ones that have really affected people’s lives. For example: “real power to change one’s life is perhaps even further outside of most people’s grasp than before.” Intuitively, the audience understands that journalists are never going to tell them “what’s going on” in the largest sense of that phrase. And this takes its toll on trust.

None of these explanations quite do it for me. I think they all have some merit, but “some” does not mean equal. I’m partial to no. 5, but I don’t think it accounts for a 28 point drop in public confidence. So that’s why I say: what would be your theory?

After Matter: Notes, Reactions & Links…

Sep. 17, 2014: Gallup: Trust in Mass Media Returns to All-Time Low. Six point drops in trust among Democrats and Republicans.

August 8, 2013: Pew Research Center returns to the subject:

Public evaluations of news organizations’ performance on key measures such as accuracy, fairness and independence remain mired near all-time lows. But there is a bright spot among these otherwise gloomy ratings: broad majorities continue to say the press acts as a watchdog by preventing political leaders from doing things that should not be done, a view that is as widely held today as at any point over the past three decades.

Aug. 16, 2012: Pew Research Center comes out with a new report: Further Decline in Credibility Ratings for Most News Organizations:

For the second time in a decade, the believability ratings for major news organizations have suffered broad-based declines. In the new survey, positive believability ratings have fallen significantly for nine of 13 news organizations tested. This follows a similar downturn in positive believability ratings that occurred between 2002 and 2004.

The Washington Post’s Ezra Klein takes up my puzzle:

I think you should see #3 and #4 as mirror images: One is the argument the right has used to erode trust in the press. The other is the argument the left has used to erode trust in the press. Both, it should be said, have their roots in real events and real grievances. The rush to war really was an example of the media — including me, as a dumb blogger in college — getting worked. But both are also the result of organized campaigns to take those real events and real grievances and turn them into a durable distrust of the media that can be activated when convenient for the two parties.

That doesn’t mean Republicans or Democrats have stopped reading, or caring about, the news media. Indeed, the loss of trust in the press has, as I understand it, coincided with a rise in the actual consumption of news media. I think we should take that revealed consumer preference for more news and news-like goods at least as seriously as we should take these poll numbers. The parties certainly do. That’s why, rather than trying to persuade their folks to abandon the media, they have contented themselves with trying to persuade them to simply mistrust the media.

Responding to both me and Ezra Klein is political scientist Jonathan Ladd: Why Don’t People Trust the Media Anymore?

I see two structural trends coming from outside of journalism as the main drivers of media distrust. First, the political parties have become much more polarized in their policy positions. Second, because of technological changes such as the rise of cable and the internet, as well as regulatory changes such as the end of the fairness doctrine, the media industry has become much more diverse and fragmented.

He also includes this chart showing the long-term decline in trust for the press as against other institutions:

One thing I don’t understand in Ladd’s post is this part: “I tend to be skeptical of any explanation for broad change that hinges of human nature simply improving or degrading. I suspect that human nature tends to be constant. Instead, I look for structural explanations. (Thus, I disagree with Rosen’s explanations #2, 3, 5, 6, and 8.)”

Human nature? I don’t get it. I don’t see how these explanations derive from a claim that human nature changed after Watergate, which is indeed absurd and unconvincing.

Ladd responds: “What I was trying to say was that journalists haven’t simply developed a greater natural propensity to behave like ‘bad actors,’ or exhibit bias, or be out of touch with the public, or co-opted by elites, or to miss scandals (like the Jayson Blair scandal) for too long, or exhibit other behaviors that we as observers might fault them for.”

Part two of Ladd’s post: Why It Matters that People Distrust the Media. Indeed.

Craig Silverman author of Regret the Error, and a student of trust construction in journalism, replies to this post with: Connecting the dots: Why doesn’t the public trust the press anymore?

Journalism that acts as the voice of God, that doesn’t listen, that doesn’t admit failings, that often punishes others for showing vulnerability does not build connection with the public.

Poynter’s resident sage, Roy Peter Clark, organized a chat with me and Craig Silverman: What can writers do to build the public’s trust in the media? The main point I tried to make is that the means for generating trust must themselves evolve.

In the comments: Clay Shirky, John Paton, Marcy Wheeler, Jeff Jarvis, Tom Watson, John Robinson, Chris Anderson, Andrew Tyndall, Roy Peter Clark and a whole lot more. Best comment thread I’ve have ever had at PressThink. (Not joking.)

The Washington Post’s Paul Farhi takes on a similar subject, but his point seems to be that there’s nothing to see here, so move along: How biased are the media, really? Not much, he seems to say, so why do people tell pollsters the opposite? He then lists possible explanations, which resemble some of mine.

James Fallows in 1996: Why Americans Hate the Media.

√ Public Trust in Government: 1958-2010.

Christopher Lydon–journalist, intellectual, radio host, and Boston presence–interviewed me when I was in Cambridge about the declining faith in American institutions, including the press. Because he is so good at what he does, it is one of the best interviews I’ve done in many years, and very much on point for this post. It will cost you 35 minutes to listen to it.

National Journal: In Nothing We Trust: Americans are losing faith in the institutions that made this country great. Loss of confidence in our major institutions is typically a social science subject. Here is a journalistic treatment that is quite good.

Clay Shirky argues that what was called “trust” in the Cronkite era was really just scarcity. And now that’s over.

Gallup chart by Terry Heaton’s PoMo blog and Audience Research & Development LLC.