It started with a Facebook post, and just kept going. If you read them in order you will be caught up with all the important plot twists. I also tried to include the key links as the story metastasized. Got a correction or addition? Please put it in the comments. Thanks.

December 11 at 4:53pm

Last night something strange came across my screen. I think it qualifies as a mystery. The news: the Las Vegas Review-Journal, largest newspaper in the state, was sold to… well, that’s the odd part. The buyer was described as a Delaware company backed by “undisclosed financial backers with expertise in the media industry.”

Undisclosed? Weird.

The name of the company purchasing the newspaper, News + Media Capital Group LLC — about which no one knows anything — is similar to the name of the company selling the newspaper, New Media Investment Group. So similar that it seems chosen to induce confusion.

(See story here, press release here.)

All this is highly unusual. Who would buy a major newspaper and not want anyone to know? What would be the possible reasons? Last night on Twitter I asked the Review-Journal: Will your newsroom be investigating the mystery of who owns you?

@reviewjournal @romenesko Will the Review-Journal be investigating the mystery of who owns it?

— Jay Rosen (@jayrosen_nyu) December 11, 2015

Today I got my answer. I received an email from a reporter at the Review-Journal, asking if I wanted to comment on “the ethics of a newspaper trying to operate without knowing who owns it.” Among the intriguing facts the reporter relayed to me: the price was $28 million more than the sale price when the same newspaper was sold in March 2015. But the newspaper’s financial fortunes had only worsened since then, a key fact.

Why is this important? Because a publicly-traded company like New Media Investment Group (holding company for Gatehouse Media) cannot legally diss an offer like that. Or let’s say: no wise corporate lawyer would advise it.

Yes! I did want to comment. Here is what I told the reporter:

It’s possible [this] has happened before but nothing comes to mind that would be comparable. As I said last night on Twitter: “Will the Review-Journal be investigating the mystery of who owns it?” and this “takes news from anonymous sources to a whole new level.”

One of the first thoughts I had was: Nevada is an early primary state. The Review-Journal is the largest newspaper in the state. Was it sold to a player in that event, or people who want to be players? That slightly conspiratorial thought may be way off base. Of course there is no way to know as long as the ownership remains hidden. That’s the point.

The simple fact that we don’t know who the owners are, that it was not announced when the transaction was announced— this in itself breeds suspicion. Because why the secrecy if it’s a normal transaction? What kind of newspaper owner doesn’t want anyone to know? Ego buyers have the opposite incentive: they want everyone to know.

Journalists already have problems with generating enough trust to operate. This just adds to it.

So now you get to see what kind of story comes out of this. I will post the link if the report ever appears. (It did.) Clearly, the journalists at the Review-Journal are as perplexed by this mystery buyer as I am.

December 12 at 11:46am

The incredible story of a major newspaper in an early primary state that now has a mystery owner continues. The publisher is refusing to tell the staff who bought the paper. The journalists are writing articles expressing their own helplessness. And no one knows what is going on, except the people who refuse to talk for reasons they refuse to reveal.

Yesterday I gave you the background in my first post. The gist: The Las Vegas Review Journal was sold this week for a weirdly inflated price to a company whose backers remained “undisclosed.” It’s the largest newspaper in the state. Nevada is an early primary state: fourth-in-the-nation. After I talked about the strangeness of this transaction on Twitter, a reporter there contacted me for a story he was doing about it. That story is now out. It includes this astounding passage:

News + Media manager Michael Schroeder has declined to disclose the company’s investors, as has Las Vegas Review-Journal Publisher Jason Taylor.

In discussions with employees, Taylor has said only that News + Media has multiple owner/investors, that some are from Las Vegas, and that in face-to-face meetings he has been assured that the group will not meddle in the newspaper’s editorial content.

Amazing… Boss, who owns us? ‘I am not going to tell you. Just go about your business. You don’t need to know.’

Here is the quote they used from me:

The timing of the transaction might also raise a question about the new owners’ possible political motivations.

“One of the first thoughts I had was: Nevada is an early primary state. The Review-Journal is the largest newspaper in the state. Was it sold to a player in that event, or people who want to be players?,” asked media critic and New York University professor Jay Rosen. “That slightly conspiratorial thought may be way off base. Of course, there is no way to know as long as the ownership remains hidden. That’s the point.”

On Twitter Saturday, The Review-Journal’s state capital reporter, Sean Whaley, wrote:

I am just going to say it. I am personally offended & embarrassed that whoever bought the RJ does not have the guts to say so #whattthehell

— sean whaley (@seanw801) December 13, 2015

Anyone who can shed light on the mystery is welcome to try.

UPDATE: It gets better: The journalists at the Review Journal are clearly in a power struggle over how this will be reported on. “The publisher of the Las Vegas Review-Journal removed quotes from a Thursday night article about the newspaper’s sale that questioned its new owner’s decision to remain anonymous, according to a newsroom source.” This is the part that was taken out:

Schroeder said News + Media does not own his newspapers or any other publications. When asked, he would not disclose the company’s investors.

“They want you to focus on your jobs … don’t worry about who they are,” Schroeder said.

Review-Journal Editor Michael Hengel noted the lack of disclosure.

“The questions that were not answered Thursday are 1) Who is behind the new company, and 2) What are their expectations?” Hengel said.

Focus on your jobs. Don’t worry about who they are. Wow.

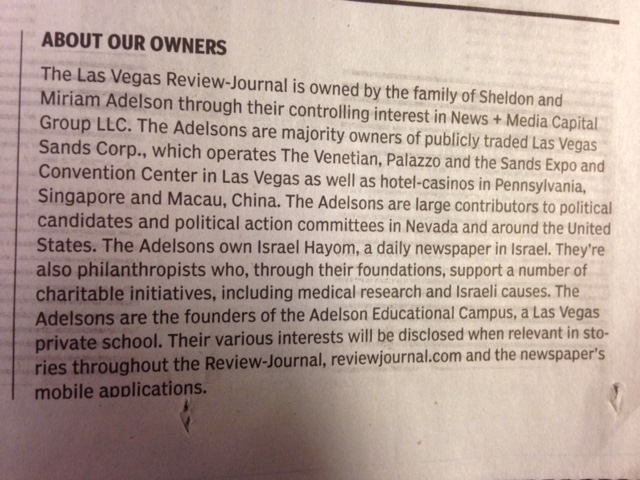

UPDATE, DEC. 13. Today on CNN’s Reliable Sources Jon Ralston, an extremely well-connected reporter in Nevada, speculated that one possibility was Sheldon Adelson, who is known to have an interest in buying a newspaper in the US, said Ralston. Adelson— billionaire, Republican mega-donor, pro-Israel extremist — already owns one paper in Israel. Ralston also said (on Twitter) “The RJ’s owners will have to reveal themselves eventually. Too much pressure. Ridiculous for them to think they can be invisible.”

December 16 at 4:06pm

Fortune magazine, citing multiple sources but not saying who they are, reports that Sheldon Adelson is, in fact, the mystery owner of the Las Vegas Review-Journal.  Yes, Sheldon Adelson Bought The Las Vegas Review-Journal.

Yes, Sheldon Adelson Bought The Las Vegas Review-Journal.

5:20 pm. Obviously, the Review-Journal has been digging too. They may have been close to naming Adelson and may be annoyed that Fortune went with anonymous sources. Pressure to go public grows for new Review-Journal owners.

8:46 pm Games: “‘I have no personal interest’ in the Las Vegas Review-Journal, billionaire casino mogul Sheldon Adelson said Tuesday night, in his first public comments about the mysterious sale of Nevada’s biggest newspaper.” CNN: Sheldon Adelson responds to speculation he bought Las Vegas paper.

10:54 pm. It’s starting to come out now. Review-Journal: Adelson son-in-law orchestrated family’s purchase of Las Vegas Review-Journal

December 17 at 11:01am

Last night was a good night for the journalism tribe. The journalists at the Las Vegas Review-Journal did their jobs, and found out who bought the paper. Their colleagues around the country were watching and cheered them on. Killer quote: “No matter who owns the Review-Journal, they don’t own us.” See: How the Las Vegas Review-Journal broke news about its own sale.

This is an important addition to the story. The Adelson camp overpaid by almost 3X for the Review-Journal, says industry analyst Ken Doctor.

UPDATE: After the revelation by others, the Adelson family published a statement in the print edition of the Review-Journal. The key parts read:

It was always our intention to publicly announce our ownership of the R-J.

This week, with each of the Republican candidates for president and the national media descending on Las Vegas for the year’s final debate, we did not want an announcement to distract from the important role Nevada continues to play in the 2016 presidential election.

Our motivation for purchasing the R-J is simple. We believe in this community and want to help make Las Vegas an even greater place to live. We believe deeply that a strong and effective daily newspaper plays a critical role in keeping our state apprised of the important news and issues we face on a daily basis.

The management team from New Media, which is currently running the R-J, will continue to oversee the operations of the publication. The family wants a journalism product that is second-to-none and will continue to invest in the paper to achieve this goal.

See: Ending Mystery, Adelson Family Says It Bought The ‘Las Vegas Review-Journal’

December 18 at 5:53pm

Incredible developments today in the ‘Sheldon Adelson buys a newspaper’ story, as the journalists at the newspaper he bought keep reporting on him— and themselves. In today’s episode they tell of a team of reporters suddenly and inexplicably ordered to stop what they were doing and instead monitor and scrutinize the work of three judges.

“One of the three judges observed was District Judge Elizabeth Gonzalez, whose current caseload includes Jacobs v. Sands, a long-running wrongful termination lawsuit filed against Adelson and his company, Las Vegas Sands Corp., by Steven Jacobs, who ran Sands’ operations in Macau.

“The case has attracted global media attention because of Jacobs’ contention in court filings that he was fired for trying to break the company’s links to Chinese organized crime triads, and allegations that Adelson turned a blind eye to prostitution and other illegal activities in his resorts there.”

The reporters did as they were told, but no story ever appeared. However a story did appear in an obscure Connecticut newspaper, owned by the same guy who served as the cutout figure (I believe that is the correct term) in the corporate filings surrounding the mystery sale: Michael Schroeder. (Link.) They write:

On Nov. 30, the New Britain Herald, a tiny Connecticut newspaper not affiliated with GateHouse, published an article critical of the performance of courts that specialize in business disputes. It singled out Judge Gonzalez with scathing criticism of her “inconsistent and even contradictory” handling of the Adelson case and another lawsuit involving Wynn Resorts Ltd…

The Adelson and Wynn cases were the only specific examples cited at length in the story. Two other judges were mentioned, but the critique of Gonzalez’s courtroom proceedings consumed more than a quarter of the 1,900-word article.

The article’s author was identified as Edward Clarkin, whose byline is found only one other time in the archives of the Connecticut newspaper, on a review of a Polish restaurant.

Attempts to locate Clarkin have been unsuccessful.

It goes on from there. See: Judge in Adelson lawsuit subject to unusual scrutiny amid Review-Journal sale.

December 20 at 2:48pm

“You can be assured that if the Adelsons attempt to skew coverage, by ordering some stories covered and others killed or watered down, the Review-Journal’s editors and reporters will fight it. How can you be sure? One way is to look at how we covered the secrecy surrounding the newspaper’s sale. We dug in. We refused to stand down. We will fight for your trust. Every. Single. Day. Even if our former owners and current operators don’t want us to.”

The journalists at the Review-Journal will not quit. That quote is from a front page editorial headlined: “We will continue to fight for your trust every day.”

Incredible. They are on their way to a Pulitzer Prize in public service, but that’s the least of it. They said to themselves: It won’t be worth working here if we don’t do this, so we may as well do this. Everyone in? And by making that decision they created tremendous power for themselves. Fight on, R-J.

See: EDITORIAL: Review-Journal will fight to keep your trust every day.

December 22 at 10:06pm

Huge news in the running story of zillionaire Sheldon Adelson’s purchase of the largest newspaper in the state of Nevada, the Review-Journal. Tonight came word that the editor has resigned. This is an ominous sign. I thought it would be the publisher. That the editor is gone is worse.

“Mike Hengel, who’s been with the Review-Journal since 2010, according to his LinkedIn profile, stunned his staff Tuesday evening when he informed them he has accepted a buyout offer. A source who was present at the meeting told POLITICO that Hengel said he didn’t believe he’d last long under the new ownership and therefore decided to consider a severance option. He told employees that the new ownership arrangement ‘had the makings of an adversarial relationship,’ according to the source.” See: Review-Journal editor steps down amid ‘makings of an adversarial relationship’

Because the Adelson forces seem ready to exert control over the Review-Journal and silence dissent, now is a good time for me to say what I heard. A team of investigative reporters similar to the Spotlight team at the BostonGlobe was to be hired at Review Journal. (It was announced here, Nov. 19.) But I was told that the journalists in the Review Journal newsroom did not know who is doing the hiring for this investigative team.

I do not know more than that, and it’s possible that this will turn out to be a minor or meaningless fact. Or there may be an innocent explanation. But since the hammer seems to be coming down, I felt I should tell you what I know. If my information is incorrect or misleading I will let you know.

UPDATE: A message from the new owners about the future of the Las Vegas Review-Journal This statement was released after news broke about Mike Hengel resigning. Key parts:

…we pledge to publish a newspaper that is fair, unbiased and accurate. We decided to buy the Review-Journal to help create a better newspaper — a forward thinking newspaper that is worthy of our Las Vegas community. This journalism will be supported by new investments in services such as enhanced fact checking and a Reader Advocate or Ombudsperson to respond to reader concerns.

Third, we regard ourselves as stewards of this essential community institution, and we promise that the Review-Journal will serve the people of Las Vegas for many years to come. In particular, we will deepen the newspaper’s involvement with the community and invest what is necessary to ensure that the R-J is reporting news in the ways our community expects.

These are the three principles that will guide our ownership of the Las Vegas Review-Journal. How will this all work over the coming weeks and months? The professionals at New Media, who are now managing the R-J as well as running more than 125 other daily newspapers nationwide, will continue to oversee all operations. Mike Hengel, the paper’s current editor, accepted a voluntary buyout offer from the R-J’s prior owners, an offer that was also made to other qualified employees.

December 23 at 5:14pm

Another amazing turn in the ‘Sheldon buys himself a newspaper’ story that I have been following for you. In this episode we discover that the top editor, who resigned yesterday, learned that he took a buyout from an editorial in his own newspaper announcing that he… took a buyout! Before that he didn’t know. I mean, why not just place on his desk a severed horse’s head? The story is in the LA Times, which considers Vegas sort of in its backyard. See: Vegas newspaper stands up to its newly unveiled owner, casino giant Sheldon Adelson.

UPDATE: The Hartford Courant picks up the portion of the story that unfolded in its backyard. Mystery Surrounds Newspaper’s Relationship To Las Vegas Casino Mogul Sheldon Adelson’s Legal Fight. The Courant reporter reveals that several people quoted in the mystery article that appeared in the Bristol Press about judges in Las Vegas never talked to the author, Edward Clarkin. Clarkin himself cannot be found, as the Review Journal revealed earlier. Even the editors of the Bristol press don’t know who he is, the Courant reported:

Jim Smith, who served as executive editor of the Herald and the Bristol Press at the time Clarkin’s first byline appeared, said he also can’t shed light on Clarkin’s identity, or how the business-court story came to be, or why the New Britain Herald was so interested in Judge Elizabeth Gonzalez. Smith said he recently reached out to Schroeder, who simply replied: “Stay tuned.”

“It’s a mystery,” Smith said. “It’s a fascinating mystery. It really is.”

UPDATE: Christine Stuart pretty much solved one of the elements of the mystery.  The author whom no one could find, Edward Clarkin, is probably the “cutout” figure in the original purchase of the Review-Journal, Michael Schroeder of Connecticut, an agent for the Adelson forces. Either that or Schroeder created the pen name that he assigned to another writer. As Stuart of CT News Junkie reports on Facebook: “Michael Schroeder’s middle name: Edward. Mother’s maiden: Clarkin.” See: How A Connecticut Journalist Broke A Key Part Of The Bizarre Las Vegas Newspaper Story (Dec. 29)

The author whom no one could find, Edward Clarkin, is probably the “cutout” figure in the original purchase of the Review-Journal, Michael Schroeder of Connecticut, an agent for the Adelson forces. Either that or Schroeder created the pen name that he assigned to another writer. As Stuart of CT News Junkie reports on Facebook: “Michael Schroeder’s middle name: Edward. Mother’s maiden: Clarkin.” See: How A Connecticut Journalist Broke A Key Part Of The Bizarre Las Vegas Newspaper Story (Dec. 29)

December 24 at 12:37pm

In today’s episode of ‘Sheldon buys a newspaper, journalists fight back’ we have a man of principle, Steve Majerus-Collins, who quits in disgust because the owner of the newspaper he works for in Connecticut is in league with Adelson and doing the billionaire’s bidding while deceiving the press and his own employees about it. From his moving letter:

I have no idea how my wife and I will get by. We have two kids in college, two collies, a mortgage and dreams of travel and adventure that now look more distant than ever.

“But here’s what I know: I can’t teach young people how to be ethical, upstanding reporters while working for a man like Michael Schroeder. I can’t take his money. I can’t do his bidding. I have to stand up for what is right even if the cost is so daunting that at this moment it scares the hell out of me.

A flurry of other action on this story today:

The Review-Journal hired a political fixer and crisis management dude who worked for Clinton and Gore among other clients: Mark Fabiani.

This piece appeared on Sheldon Adelson’s newspaper in Israel and how it’s run.

And Michael Schroder, the Adelson flunkie and cutout figure who tried to keep the billionaire’s ownership secret (while telling the Review-Journal staff not to worry about who owns them) would not confirm his mother’s maiden name to journalists from the newspaper he “manages.” That’s right.

December 25 at 7:00pm

In today’s episode of the Adelson newspaper follies we learn that Sheldon’s flunky and cutout figure Michael Schroeder — described by an employee who quit yesterday (Steve Majerus-Collins) as “guilty of journalistic misconduct of epic proportions” in that he “used the pages of my newspaper, secretly, to further the political agenda of his master out in Las Vegas” — has purchased another paper to add to his toy collection.

The tiny Block Island Times will now belong to Schroeder personally. The comic touch was provided by the statement that the sellers issued.

“We are confident that the new owner, Michael Schroeder, has the vision, resources and experience to take the helm,” the statement said. “We are pleased that his wife, Janet, will also play a role in the day-to-day management. They offer decades of business experience. Most importantly, they exhibit in their employment and volunteer work, a commitment to the community and its betterment.”

I might have added, “he would make an excellent bag man.” (Definition of the term bag man here.)

December 26 at 5:25pm

For today’s episode of the Adelson newspaper follies we bring in a guest commenter, Josh Marshall, editor of Talking Points Memo, who wrote about the whole sad story yesterday. Says Josh:

“I have an obvious interest in journalism and the journalistic profession.  Perhaps not much less obviously I have a taste for scandals that are not merely outrageous but are baroque in their complexity and rise above mere bad acts to reach the more sublime human qualities like impulsiveness, greed that goes beyond mere greed, hasty efforts to cover up wrongdoing which take on a level of comedy that could never emerge from conscious design. Here is where we are getting to the level of scandal as art. And this is why Michael Schroeder is really the star of this whole show for my money.”

Perhaps not much less obviously I have a taste for scandals that are not merely outrageous but are baroque in their complexity and rise above mere bad acts to reach the more sublime human qualities like impulsiveness, greed that goes beyond mere greed, hasty efforts to cover up wrongdoing which take on a level of comedy that could never emerge from conscious design. Here is where we are getting to the level of scandal as art. And this is why Michael Schroeder is really the star of this whole show for my money.”

I agree. Schroeder the cutout turns the interest dial up to 11. Read Josh’s entire piece:

And I have to add: I have the same taste for the baroque element in a running scandal. In fact, I learned the iterative technique I have been using in this series of posts from… Josh Marshall, during the US Attorneys Scandal in 2007, for which he won the George K. Polk Award. I remember how he would always have something to read each day. If there was no new information he would use the opportunity to reflect and summarize. Very effective means of engagement.

UPDATE: Reporter Who Resigned Over Adelson Subterfuge Gets $5,000 Award.

December 27 at 11:50am

Our series — Adelson tries to corrupt the press, journalists fight back — continues today with a piece by Las Vegas Review-Journal columnist John L. Smith. Like Josh Marshall yesterday, Smith focuses on the hilarious and disturbing figure of Michael Schroeder, the Adelson flunky who told the Review-Journal newsroom just to do their jobs and not worry about who bought their newspaper for 3 times market value. Smith writes:

“Schroeder’s journalistic puppetry in preparing an inaccurate story about business courts meant primarily to smear District Judge Elizabeth Gonzalez, who happens to preside over a bruising ongoing litigation involving Adelson, sends a disturbing message to the staff and readers alike. The story, published in Schroeder’s New Britain newspaper, raises serious questions: Not about Gonzalez’s competence, but about Schroeder’s veracity.

“Under the byline ‘Edward Clarkin,’ almost certainly a Schroeder alter ego, the piece contains an inaccurate appraisal of the judge and sections that appear to have been lifted without proper attribution, or created from whole cloth. The Hartford Courant reported the article contained ‘several passages that are nearly identical to work that previously appeared in other publications.’

“Ill-conceived, poorly executed. Nice job, Hemingway. To call the story ham-handed does a disservice to ham.”

There have been several indications that journalists around the country continue to dig into this story. I’m waiting for someone to start asking questions and getting answers about Gatehouse Media’s role in this spectacle. This is a company that apparently sent investigative teams after Adelson’s target before the billionaire’s purchase of any assets. What’s up with that?

December 28 at 12:14pm

Two items for today’s update in the ‘Adelson buys a newspaper, journalists fight back’ story. First, I am going to be on the radio talking about it. Remember radio?

Today at 1:00 pm EST I will be on the Colin McEnroe Show on WNPR, public radio in Connecticut, along with Steve Majerus-Collins, who on Christmas eve quit his job as a reporter for the Bristol Press, owned by Adelson flunky and cutout figure Michael Schroeder.  Quit on principle, I should add.

Quit on principle, I should add.

“I have learned with horror that my boss shoveled a story into my newspaper – a terrible, plagiarized piece of garbage about the court system – and then stuck his own fake byline on it,” he wrote. “I admit I never saw the piece until recently, but when I did, I knew it had Mr. Schroeder’s fingerprints all over it. Yet when enterprising reporters asked my boss about it, he claimed to know nothing or told them he had no comment.”

I don’t know what Colin McEnroe has in mind for this discussion but it should be interesting to hear from Steve. Here’s the preview, with an audio link so you can listen to a recording of the show.

UPDATE: One thing new I learned from the show. Steve Collins said that Michael Schroeder had a backer when he bought the Bristol Press. He didn’t make the purchase with his own money. The host asked him: who? Steve didn’t know and said no one in the newsroom knew. This detail, which I had missed, was reported Dec. 15 by the Review Journal.

The other item I have for you comes from the New York Times article today about the whole sad story, which more or less repeats what others have reported. But there was one part so deliciously absurd that I cannot let it escape without comment.

You see, the Adelson forces earlier decided that they were losing control of the story. So they hired a semi-famous fixer and crisis management expert to handle national press interest, which keeps growing. His name is Mark Fabiani. He’s worked for the Clintons, Al Gore, and the owner of the San Diego Chargers, among others. No doubt he’s earning hundreds of thousands of dollars for this gig. So here’s what the Times reported:

“To deal with the fallout from its Review-Journal purchase, the Adelsons have hired Mark Fabiani, a crisis communications specialist who worked in the Clinton White House and for the cyclist Lance Armstrong. Mr. Fabiani did not respond to inquiries about whether the issue of Nevada judges came up during sales talks.”

Did you catch that? He did not respond! To the freakin’ New York Times! That’s crisis management? The clever application of Mark Fabiani’s “no comment” skills? I bet it cost Adelson 15 grand just for that. Heck, I could do it for a lot less— say, $10,000 for every phone call unreturned. I have three phones (home, cell, office) from which I could ignore reporters’ calls, so I think I am more than qualified to do what Fabiani does.

Surreal.

Dec. 29 at 4:21pm

In today’s episode of ‘the Adelson forces buy a newspaper,’ we learn that the Nevada Gaming authorities, state regulators for the gambling industry, are keeping a close eye on the purchase of the Review-Journal. We also learn that Sheldon Adelson himself denies owning any portion of the newspaper or even wanting to. It was his children’s idea, he says. All this in the latest report from the Review-Journal itself.

“We are watching all of these developments very closely,” a state official said. “Of course, it’s incumbent upon all gaming license holders to avoid actions that go against the morals, good order and general welfare of the people of the state of Nevada, and to avoid doing anything that reflects or tends to reflect discredit on the state.

“I’m sure Mr. Adelson and his team are doing their utmost to do that.”

Me too!

Speaking of morals, Adelson told the Macau Daily Times that “his children” bought the Review-Journal and he has “no financial interest” in the newspaper.

“I don’t have anything to do with it,” Adelson said. “My money that the children have with which to buy the newspaper is their inheritance. I don’t want to spend money on a newspaper.”

Meanwhile, in yesterday’s radio discussion on WNPR in Connecticut, James Wright, deputy editor of the Review-Journal, said “we’re not sure who’s in charge.” Things happen — including changes made in stories after they leave the newsroom — “at whose behest we don’t know,” said Wright.

“Strings gets pulled but at this point we are often unaware whether it’s something that Gatehouse wants to do, whether it’s something the Adelson family wants to do, or whether its somebody within this daisy chain of ownership and managers who may be taking it upon themselves to overreact to something that they think someone wants to do.” That’s pretty chilling. (Listen here.)

It’s clear to me that Gatehouse Media has to be the focus of some serious inquiry by fellow journalists now. The company is becoming an engine of opacity in this story and since it is a news company that is both a curiosity, and a problem.

Dec. 30 at 10:29am

Today’s update in the ‘Adelson forces buy a newspaper’ story focuses on a player that has gotten too little attention: GateHouse Media, a resurrected chain of newspapers (it went bankrupt in 2013) that used to own the Review-Journal. Bear with me as I explain:

On December 10th the announcement was made that GateHouse had sold the Las Vegas Review Journal to a shell company called News + Media Capital Group LLC. It then cooperated in concealing the true nature of this transaction from public scrutiny. (First dark cloud.)

GateHouse was retained by the Adelson family to continue to operate the newspaper, but since then strange things have happened to various articles the Review-Journal newsroom has prepared about the sale and suspicious circumstances surrounding it. The work of the journalists in Las Vegas gets changed before it is published, but no one in the newsroom knows why, or how, or by whom. As deputy editor James Wright said Monday on WNPR’s Colin McEnroe show:

GateHouse was retained by the Adelson family to continue to operate the newspaper, but since then strange things have happened to various articles the Review-Journal newsroom has prepared about the sale and suspicious circumstances surrounding it. The work of the journalists in Las Vegas gets changed before it is published, but no one in the newsroom knows why, or how, or by whom. As deputy editor James Wright said Monday on WNPR’s Colin McEnroe show:

“Strings gets pulled but at this point we are often unaware whether it’s something that Gatehouse wants to do, whether it’s something the Adelson family wants to do, or whether its somebody within this daisy chain of ownership and managers who may be taking it upon themselves…” (Second dark cloud.)

This is why I have called GateHouse an engine of opacity in this story, which is troublesome for a newspaper company that counts 125 dailies among its holdings. Yesterday, a journalist who once worked for a GateHouse publication, Kris Olson, posted this on my Facebook page. I thought it pretty compelling so I am highlighting his words:

I could go on at length about this subject, but as a former and future Gatehouse employee (Gatehouse has an agreement to buy the paper I currently work for in the new year), I should probably hold my fire to some degree. But I do hope Gatehouse realizes the impact of being an ‘engine of opacity,’ as you aptly put it, has on the morale of the journalists it employs. Go to gatehousenewsroom.com, and you’ll see a lot of high-minded talk about ethics in and among discussion of the company’s editorial strategy. But you can’t just talk the talk. You have to walk the walk. After all, the whole reason someone hired a lot of us, I presume, is that we have well-honed B.S. detectors (as the Review-Journal staff and others have proven time and again over the past couple of weeks). Those of us who have stuck with the profession through no pay raises, unpaid furloughs, reduced staffs, etc., etc., really need to at least cling to the idea that our bosses, on some level, get it. That they don’t wear the black hats. Steve Collins was left with no other choice but to conclude that his boss indeed didn’t get it, and indeed wears a black hat. I’ll echo many others who have lauded his brave, principled decision. As of now, I feel like Gatehouse employees are sort of in limbo. I’m not 100-percent convinced that they are in Collins’ position, but I’m not 100-percent convinced that they aren’t. But I do feel pretty strongly that Gatehouse can’t just hope this will blow over. They hired us for our long memories, too. (Third dark cloud.)

Gatehouse Media is the one who ordered R-J journalists to investigate three Nevada judges, one of whom turned out to be the presiding judge in a lawsuit against Sheldon Adelson’s company. When asked about it by reporters, Michael Reed, CEO of New Media Investment Corp., the parent company of GateHouse Media, declined all comment on whether Adelson was involved. That was a real confidence builder!

Reed said the effort was part of a “multistate, multinewsroom” investigative effort initiated by GateHouse. Really? What was this project all about? Reed said he did not know who started it or who approved it. Weird. Big investigative efforts are launched but nobody at this company knows why, or who gave the order.

“I don’t know why you’re trying to create a story where there isn’t one,” Reed told an R-J reporter. “I would be focusing on the positive, not the negative.” An incredible —and threatening — statement for a news company executive to make to a journalist pursuing a legitimate story. (Fourth dark cloud.)

Then there’s this from GateHouse CEO Kirk Davis when the sale was announced:

The Review-Journal and other Nevada newspapers are the first outlets GateHouse will manage for a company other than New Media Investment.

“We look at this as a possible new business model,” said Davis, who told Review-Journal employees he hoped the management agreement would be long-term.

Uh… really? A new business model? You mean there are other billionaires out there who want to pay three times market value for one of GateHouse’s newspapers, and then hire the company back to run them? Does that sound remotely plausible? (Fifth dark cloud.)

I hope you see what I mean by an engine of opacity. Its time for GateHouse to come under national scrutiny for its role in this lurid, comic and credibility-crushing affair.

Jan. 3 at 8:08pm

A new article appeared yesterday in the New York Times under the headline: ‘Sheldon Adelson’s Purchase of Las Vegas Paper Seen as a Power Play.’ No kidding! Several things in it I found noteworthy:

1. New policy: “The paper’s publisher, Jason Taylor, now requires reporters and editors to get written permission before any article regarding The Review-Journal or Mr. Adelson’s purchase of it is published.”

We don’t know why this is. We don’t know who is insisting on it. We do know that the R-J newsroom has been aggressive in covering this story, and that sometimes things get changed in articles prepared by the journalists there. No one knows where the interference is coming from.

“Must get written permission” sounds like an attempt to clamp down on the Review-Journal’s drive to break news about the Adelson back story. That makes investigative work by other newsrooms even more important, but it’s likely that the out-of-town press will get bored and moved on.

2. The comments of the Las Vegas mayor, who was interviewed for the story. “When you have all the marbles, you can make the calls,” said Carolyn Goodman, the mayor of Las Vegas, about billionaire Sheldon Adelson. “And he has all the marbles.”

Remarkable statement, since it essentially admits that money talks, and the political system listens and obeys. While this is not shocking news — no, I am not surprised by it — it is a little weird for the person at the top of the political system to confess to such helplessness. About Adelson’s purchase of the newspaper the mayor said: “I’m very excited he’s done it.” Excited? Really? That’s odd.

3. “He’s done it,” the mayor said. Notice the “he” there? The mayor assumes that the purchaser is Sheldon Adelson himself. The same assumption is made by Mark Fabiani, described in the Times article as “a crisis management expert and a spokesman for Mr. Adelson.” Fabiani compared Adelson to other billionaire purchasers of newspapers: Jeff Bezos (Washington Post) and John Henry (Boston Globe.)

Why does this matter? Because Adelson himself denies that he is the purchaser. He says he doesn’t even want to own a newspaper. “I don’t have anything to do with it,” Adelson told the Macau Daily Times. “My money that the children have with which to buy the newspaper is their inheritance. I don’t want to spend money on a newspaper.” So, Fabiani is in effect making a liar out of his client. In the New York Times! Nice job, Mr. Crisis Manager. Smooth.

4. Weirdly, the Times article says nothing — not a word — about the bizarre article that appeared in the Bristol (Connecticut) Press criticizing the behavior of Judge Elizabeth Gonzalez of Nevada, after journalists at the Review-Journal were told to investigate her. I’m not sure what to make of this. The Bristol Press is run by Michael Schroeder, the cutout who fronted for Adelson in the mystery purchase, back when he was trying to conceal it.

5. By far the most mysterious and significant events in this entire story involve another player not mentioned in the Times article: GateHouse Media, which sold the R-J to Adelson for a hugely inflated price. The events are mentioned, but not GateHouse itself. Here is how the Times article begins:

“Two days after Sheldon Adelson’s lawyers lost in their attempts to have a judge removed from a contentious lawsuit that threatens his gambling empire, a call went out to the publisher of this city’s most prominent newspaper.

“Almost immediately, journalists were summoned to a meeting with the publisher and the general counsel and told they must monitor the courtroom actions of the judge and two others in the city. When the journalists protested, they were told that it was an instruction from above and that there was no choice in the matter.”

We still don’t know who gave that order, or why. No one has been able to shed light on this “instruction from above.” But the Times reports that it “came in the first week of November, as negotiations on the sale were drawing to a close.” This is where journalistic effort should be focused now: on what GateHouse media thought it was doing by ordering that investigation. See my comments here.

6. I don’t know what to make of it, but I need to mention an anonymous comment received at this site by someone who claims to know some of the major players in this case. “Adelson has used this tactic before when he asked Jacobs to secretly spy on Macau government officials,” this person writes.

Steve Jacobs is the former executive for Adelson’s company in Macau who is involved in the wrongful termination lawsuit being heard by Judge Elizabeth Gonzalez. In his court filings he refers to “Adelson’s direction to me to have investigative reports prepared on Macau government officials as well as certain junket representatives reputed to have ties to Chinese gangs known as triads.” The whole comment is worth reading, though as I said I don’t know how much trust to put into it.

January 4 at 11:45pm

As I told you it must, attention has finally turned to GateHouse Media, the company that sold the Las Vegas Review-Journal to Sheldon Adelson for a wildly inflated price. Also the company that ordered journalists at the R-J to investigate a local judge presiding over a sensitive lawsuit against Adelson’s business empire. Also the company that becomes tongue-tied and non-communicative in the extreme when anyone asks about that investigation. Also the company that says it doesn’t know how it happened, or who ordered it, or why, or gives non-sensical answers to those questions. What we do know is that the orders to investigate the judge came during the negotiations that led to the sale of the newspaper to Sheldon Adelson.

Now on to what happened today.

First, the Review-Journal reported that Michael Schroeder of Connecticut, the bumbling cutout figure who was named “manager” of the newspaper when the sale to Adelson was first announced, will have no role from here on. To observe that Schroeder has zero credibility in the news business would not be fair, because the actual figure is less than that. He appears to be a plagiarist as well as a toady for Adelson, and he has been unwilling to assume any responsibility for his idiotic actions, or even acknowledge that they were his.

These include placing into his tiny newspaper in Connecticut a highly suspicious article attacking the Las Vegas judge whom Gatehouse  had forced its journalists to investigate, using a phony byline to do it, and when found out acting like he knew nothing about it or can’t comment when he was almost certainly the author and agent of these acts.

had forced its journalists to investigate, using a phony byline to do it, and when found out acting like he knew nothing about it or can’t comment when he was almost certainly the author and agent of these acts.

“I didn’t want any tie between that scandal and this newspaper,” said the publisher of the Review-Journal, Jason Taylor. “I didn’t want anyone to think that (Schroeder) would be attached in any way to our newsroom. I don’t want our peers in journalism or members of the public to feel like our journalism has been compromised.”

Hold it right there, Mr. Taylor. Just… stop. In fact there is a tie between Schroder’s fakery and the Review-Journal because the company that employs you to be the chief executive of the Review Journal, GateHouse Media, forced your journalists to investigate that judge, the same judge Schroeder attacked in his bizarre Dec. 1 article. You’re saying you know nothing about this? The orders “from above” must have come through you. And every time you are asked about it you have nothing to say.

Which gets to another thing that happened today. Ken Doctor, a former newspaper journalist who has become a well-sourced writer on the media business and analyst of the newspaper industry’s faltering economics, came out with a column in which he says that GateHouse executives realize they’re in deep trouble. Doctor writes:

“Executives at [Gatehouse] can be accurately described as ‘horrified’ — thankfully and properly — by the many missteps involved in the Adelson sale. Company leadership’s first instinct was to hire a crisis management expert. Now it has come to realize that the problem of Las Vegas could more widely affect the view of whole company. The company must now assert its editorial principles overall, GateHouse management has come to believe.”

On Twitter I told Ken that I had seen no signs of this realization, so he must be referencing confidential conversations he had with GateHouse leadership. He said he was, and that the evidence of this new attitude would be what the company does in the days and weeks ahead. I suppose getting rid of the pathetic Schroeder could be a sign but he was never a GateHouse person. He worked for the shell company Adelson created to obscure his purchase.

As Doctor wrote: “It appears that Adelson, or his people, tried to commandeer R-J investigative resources to ‘monitor’ the performance of local judges who have been thorns in Adelson’s backside.” That’s a big deal. “Even before the legal transfer of the paper had been inked, Adelson, with GateHouse management help, had trampled traditional journalistic lines and convention, believing he could use journalists as a hit squad.”

I would go further: There appears to have been a quid pro quo. Adelson would overpay for the property, adding handsomely to GateHouse’s bottom line and making the executives look like investment wizards. In return, GateHouse would assemble its hit squad and go after the judge for Adelson.

Ken Doctor’s prescription: “GateHouse must move quickly to appoint a respected editor, known for journalistic integrity. Further it owes the wider community — in Las Vegas and nationally — a set of basic principles, putting in public writing the commonsense standards of fairness that drive, though unevenly, American daily journalism. Finally, it should publish a public accounting of the December mess.”

Would an editor with integrity take that job? I have doubts about that.

A third thing happened today: GateHouse sent an editor from one of its other papers, the Providence Journal, to Las Vegas to try to work out with the staff at the Review-Journal some principles for how to report on the Adelson family and issues Adelson is involved in. The Providence editor, Dave Butler, met with the newsroom. It did not go well.

An editor for the R-J, Stephanie Grimes, live tweeted the meeting. Peter Sterne, a reporter for Capital New York, collected her tweets and summarized the meeting as follows: “The Providence Journal executive editor tells Review-Journal editors that they don’t need to cover their new owner so aggressively. The editors are skeptical.”

Butler, of course, claimed that this was not his intent and not what he said.

UPDATE: Michael Schroeder apologized to readers of the Bristol Press today. But like the upstanding character that he is… he did not put it online. I reproduced it here. Tomorrow’s update will include my commentary on this text.

Finally: if you’re coming to the story for the first time, just go to the top of this post and read from there. If you have a First Amendment heart you will be amazed— and depressed.

January 6 at 11:20am

In today’s episode of ‘Adelson buys a newspaper, journalists fight back’ we deconstruct a note to readers published yesterday by Michael Schroeder in the Bristol Press. It was presented as an apology and mea culpa. But it is neither of those things. Schroeder only pretends to take responsibility. His apology is fake. Not the “I’m sorry if you were offended” kind of fake that we’re so used to seeing on the internet. More the “if I admit what I did I would have to resign and disappear in disgrace but I’m not strong enough to face that right now and besides there’s no one to make me…” kind of fake. Is there a word for that? I guess denial will have to do, but that might be giving him too much credit.

If you don’t know who Michael Schroeder is, or how he figures in Sheldon Adelson’s covert purchase of the Las Vegas Review-Journal, or why he was banished from that newsroom this week, or why he needed to apologize to readers of a small Connecticut newspaper for which he serves as editor and publisher, go read this (it’s an amazing story) and come back.

Schroder’s apology fails before it starts for a simple reason: it’s not on the internet, only in print. When you truly want to apologize for something you published, one of your concerns is how to reach the people who were reached by the thing you should not have said. The fraudulent and nearly unreadable article Schroder published on business courts — so he could slip in an attack on a Nevada judge presiding over a law suit against Adelson’s business empire — can still be found on the internet. His apology cannot. When people search on his name it won’t come up. But when reporters call him to ask questions (because many are left unanswered) he can say he dealt with the issue and is moving on. That’s the kind of man he is.

Before you can apologize for what you did you have to describe it. Otherwise how does anyone know you realize what you did? At this basic human task, understood by middle schoolers across the globe, Schroeder fails completely. A few examples among many I could cite:

* Several people quoted in the article were contacted by Hartford Courant reporter Matthew Kauffman about their quotes. They said they never talked to “Edward Clarkin” whose name appears on the story, and they certainly never talked to Schroeder. Journalistically speaking, that’s fraud. What does ‘note to our readers’ say about this practice? Nothing.

* One of the people contacted by Kauffman said he was not even an expert in the subject he was quoted upon:

Arwood said he doesn’t know where that quote came from. “I saw this come through our clips and do not recall ever being interviewed and have no understanding of the issues and Michigan does not even have this type of [business-court] system,” Arwood said.

Fraud x stupid = Schroeder. What does ‘note to our readers’ say about it? Nothing.

* In addition to fake quotes (a firing offense if you’re not the boss) Schroeder appears to have plagiarized from a law review article and the Huffington Post. What does he say about it? Passive voice! “Pieces of the article were taken from related Internet sites and were not credited.” Really? By whom? “Our policy is always to credit the news organization [we take stuff from]… This was not done with this story.” Right. Bad things were done, but no one did them.

* One of the comic elements of this story is the use of a fake name, Edward Clarkin. That’s how Schroeder got caught; no one could find this person. Plus, Edward is his middle name and Clarkin his mother’s maiden name, so again: multiply fraud by stupid and you get Michael Schroeder. What does ‘note to our readers’ say about it? Here Schroeder reaches beyond the silent and the stupid to the sublime, for this is his explanation:

It was a combination of writing and reporting from multiple sources, with anonymity promised, in this case inappropriately. That’s why a pseudonym — “Edward Clarkin,” which had been used before — was used in this instance.

Appreciate what he’s saying here: because “Edward Clarkin” promised his sources anonymity he had to remain anonymous! Uh… that’s not how it works. That’s the opposite of how it works. If your sources remain anonymous we have to know who you are, because we can’t get in touch with them. Anyway, Schroeder can’t even admit that he is Edward Clarkin, or tell us who Edward Clarkin really is. A fake name “was used.” By whom? He knows, but he won’t say.

* The fraudulent article claims that experts were consulted. It uses weasel words like “many say.” It notes that lawyers in Las Vegas didn’t want to go on the record. But it doesn’t actually quote a confidential source. Yet the people it does quote say they never talked to any reporter from the publication in which they are quoted. In normal practice when journalists use confidential sources, readers get the quotes but they don’t know who these people are. In Schroeder’s way, readers know who they are, and the sources don’t know they were quoted! Innovation, of a kind. Alas, the invention will be short lived. Schroder says simply: “We have eliminated this practice.”

* On Dec. 23 Schroeder was asked about some of the problems I have listed here. His reply then: “We stand by our story, and invite anyone who believes we published something in error to call our attention to it.” Why did he say that two weeks ago if now he’s saying that the story failed to measure up “to the high degree of journalism to which we are dedicated?” What crumbled in his stone wall? The note to readers doesn’t say.

* By far the most important thing Schroeder could have done in this note is explain the nature of his relationship to Sheldon Adelson, how his name ended up on incorporation papers for the shell company created when the Adelson family purchased the Review-Journal in Las Vegas, what the connection was between this fraudulent article he’s apologizing for and the agreement he struck with Adelson, and finally: why does a small community newspaper in Connecticut have such interest in the rulings and courtroom behavior of Nevada 8th District Judge Elizabeth Gonzalez? What did Schroeder as editor hope to achieve by publishing this crap?

These are the mysteries that have brought press attention to Michael Schroeder. About these central questions his note to readers has nothing to say. Here’s what it does say:

A part of the story involved a matter concerning the buyer of the Las Vegas Review Journal. There should have been a tag line indicating that I have a business relationship with that person.

That person? Don’t utter his name because then people might actually begin to understand what is going on here. Schroeder concludes by saying he takes “full responsibility” for “these failures” but I hope you see by now: that is a pathetic lie.

Here’s the Review-Journal’s coverage of the Schroeder mea culpa, in which I am quoted. It has some additional information on what’s missing from the note.

Here’s a report on GateHouse Media’s attempt to come to some agreement with the Review-Journal newsroom over rules for reporting on Adelson. They actually made progress on some reasonable guidelines.

Here’s an appreciation of Steve Collins and Jackie Majerus by Nat and Nick Hentoff. Both quit working for Schroeder when they realized what an unprincipled man he was.

Here’s a more genuine apology from the billionaire owner of the Boston Globe, John Henry, for massive problems the Globe has been having with print delivery.

Finally: Mark Fabiani, the crisis management expert who was hired to handle press interest in the Review-Journal mess, has compared Sheldon Adelson to John Henry. The point being that billionaires can be good owners for struggling newspapers. But I don’t think much of that comparison, since Henry is out there apologizing for major screw-ups and Adelson can’t even admit that he owns the Review-Journal. His children bought it, he says. He has nothing to do with it, he says. Conclusion: He and Michael Schroeder deserve each other.

January 11 at 12:35 pm

Some juicy new details have emerged in the story of bumbling cutout figure and Adelson flunky Michael Schroeder, editor and publisher of the New Britain Herald and The Bristol Press in Connecticut. They involve the fraudulent and ill-fated article with the byline of a fictional character, Edward Clarkin, which he published on November 30. The article criticized Nevada judge Elizabeth Gonzalez, who presides over a sensitive court case in which Sheldon Adelson’s casino empire — the source of his wealth — is being sued.

Two days before that article appeared, Adelson’s lawyers had failed in their attempt to have the judge disqualified for bias. As I wrote in my previous update, Michael Schroeder recently apologized for that article without really explaining how it came to be— or even mentioning Adelson’s name. But now we know a bit more, thanks to investigative reporter Peter H. Stone’s account in the Huffington Post.

Stone has found out that Schroeder tried to get a former reporter for his Connecticut paper to take on the hit piece about the Nevada judge and offered him a lot of money to do it:

“Three months before a mysterious article popped up in an obscure Connecticut newspaper criticizing a judge overseeing a lawsuit against Republican mega-donor Sheldon Adelson and his casino empire, freelance reporter Scott Whipple received a lucrative proposal from his old boss.

“Meeting at the small paper’s New Britain offices, publisher and editor Michael Schroeder offered Whipple $5,000 to write a piece about Nevada judicial decisions.

“This was unusual, to say the least. Whipple, a veteran business reporter who had recently retired, had accepted some freelancing projects from his former employer, but Schroeder had never offered him a sum that large before. And the assignment seemed completely unrelated to the usual issues covered by the New Britain Herald and its sister paper, The Bristol Press.”

Whipple turned it down because it smelled funny. Adelson’s name was mentioned in the offer, he said. (A key fact.) We still have no clear idea how the project began or why the ‘Edward Clarkin’ article ran. But some things we do know:

At least three times journalists were asked to take on this assignment and thought it smelled bad. The first was around September 1, when the project was dangled before Scott Whipple by Schroder, according to Stone’s report. Two months later GateHouse Media, the previous owners, tried to get their investigative team in Florida to look into Nevada judges. Bill Church, top editor of the Sarasota Herald-Tribune, said he got a call in early November about “a potentially big story regarding the court system and potential ethics violations,” as he told the Las Vegas Review-Journal.

The call came from David Arkin, GateHouse’s vice president of content and audience. Church resisted the assignment, in part because GateHouse owned the Las Vegas newspaper. Why were they asking a Florida team to take on an investigation of Nevada judges if the company had its own journalists in Nevada? GateHouse stood down from that request. What the editor in Sarasota did not know is that his company was then negotiating with the Adelson family to buy the Review-Journal through a shell company called News + Media Capital Group LLC, with Michael Schroeder of Connecticut as front man.

The third time the project smelled bad to journalists began November 6 when GateHouse ordered the Review-Journal reporters to drop what they were doing and “monitor” three Las Vegas judges. “The initiative was undertaken without explanation from GateHouse and over the objection of the newspaper’s management, and there was no expectation that anything would be published,” the Review-Journal later reported.

An interesting detail in that report: GateHouse, the article said, did not specify that Gonzalez had to be one of the judges. “She was selected at the RJ — though not within the newsroom — because she specializes in business lawsuits and is handling unrelated high-profile cases involving Adelson and fellow casino mogul Steve Wynn.” My italics. That phrase, “though not within the newsroom,” probably means the publisher or the newspaper’s attorney specified Gonzalez. The Review-Journal reporters are letting us know: we didn’t do this! It came from above.

Another thing we know is that every time someone in a position of responsibility is asked about the origins of the Nevada judges project they either clam up or start saying strange things. Some examples:

* “Why would a local paper in New Britain devote so much space to dissecting the rulings of a county judge 2,288 miles away? And who is the mysterious ‘Edward Clarkin’ whose name appears as the author of the Herald story? Those questions have been swirling for days in journalistic circles, but they will not be answered by Schroeder. “I have no comment on our newsgathering, story selection or writers, as always,” Schroeder said in an email.” (Hartford Courant, Dec . 23)

* This paragraph in Stone’s story is a gem because it is so in character for Schroeder: “In three phone interviews in recent weeks, Schroeder declined to answer well over a dozen queries, including questions about the genesis of the story and whether he knew Edward Clarkin. Asked if he valued openness and transparency in the media, he replied, ‘Absolutely.”

* “To deal with the fallout from its Review-Journal purchase, the Adelsons have hired Mark Fabiani, a crisis communications specialist who worked in the Clinton White House and for the cyclist Lance Armstrong. Mr. Fabiani did not respond to inquiries about whether the issue of Nevada judges came up during sales talks.” (New York Times, Dec. 27.)

* “For a week, Mr. Fabiani repeatedly declined to respond to questions about whether Las Vegas judges were discussed during sales talks. But he said in a written statement that The Review-Journal had reported on business cases before Mr. Adelson was involved, and the newspaper did not publish any articles based on the journalists’ monitoring of the judges.” (New York Times, Jan. 2) When the best thing you can say about the assignment is “Hey: we didn’t publish anything!” that… signifies.

* Only once, as far as I can tell, did the people who know let their guard down and try to explain the Nevada judges assignment. This is from the Review-Journal, Dec. 19:

Reached by telephone Friday, Arkin said he was getting on a plane and would have to call back. Hours later, Arkin emailed a prepared statement defending the company’s request for the Sarasota paper’s help as well as GateHouse Media’s newsroom ethics to Hengel, Wright and reporter Eric Hartley.

GateHouse was “engaged to tackle an investigative story in Las Vegas with no knowledge of the prospective new buyer. Because Las Vegas was relatively new to the company, we decided to approach our newsroom in Sarasota, Florida, a team that is known for tackling big investigative journalism,” the statement reads in part.

“On the face of the situation, we had what appeared to be a great story we were capable of investigating, and I wanted our team to show its talent. From my point of view, it was nothing more.”

Here’s the big tell in that: GateHouse was engaged to investigate this story? By whom? That suggests Gatehouse is acting at the behest of a third-party, like when a law firm is engaged by a client to handle a messy legal dispute. But GateHouse is owner-publisher-commander of its investigative teams. It doesn’t loan them out to others, right? We were engaged to tackle this big investigative story and we wanted our people to shine— doesn’t that almost give the game away?

This is probably why “no comment” and “would not return calls” is all anyone has had to say since then. Also if this was such a great story what happened to it? Why didn’t the company’s own talent see it that way?

Look: Michael Schroeder knows why he offered freelancer Scott Whipple $5,000 to write a piece about Nevada judicial decisions. He just won’t say. David Arkin, GateHouse’s vice president of content and audience, knows why he asked the editor in Sarasota to take on an assignment in Nevada. He knows who “engaged” the company for that purpose. He just won’t say. Unless he’s completely incompetent, Kirk Davis, CEO of Gatehouse Media, knows what this is all about. He just won’t say. Fixer Mark Fabiani knows that he’s not supposed to go there at all, probably because this is a situation that cannot be fixed, or even fudged.

January 26 at 2:00pm

I didn’t know anyone was asking Michael Schroeder to teach journalism. He’s the cutout figure in the stealth sale of the Las Vegas Review Journal, the publisher of a bungled hit job on Nevada judge Elizabeth Gonzalez in his small Connecticut newspapers, and the keeper of secrets about his dealings with billionaire Sheldon Adelson. (Including ‘who is Edward Clarkin?’) But he’s not teaching journalism any more.

Last night I learned from the Facebook page of Steve Collins, who used to work for Schroeder but quit in disgust, that last month Schroeder had resigned from his slot as a part-time instructor at Central Connecticut State University’s journalism program. Today I talked to the student who broke the news in the school newspaper, Christopher Marinelli, and several other people involved in these events.

Schroeder was supposed to teach an editing course and help supervise CCSU journalism students on a reporting trip to Cuba later this term. Marinelli had been following closely the story of the Adelson empire, Michael Schroeder and ‘Edward Clarkin,’ the fake name Schroeder put on this botched and almost certainly plagiarized article, published Nov. 30 in the New Britain Herald.

Marinelli, a 20 year-old journalism and linguistics major from Plainville, Connecticut, had worked at the Bristol Press, one of Schroder’s newspapers, as a summer intern and part-time writer. On Dec. 23 he told his editor he could no longer work at the paper, as Steve Collins reports.

Chris Marinelli didn’t think Schroeder should be teaching editing at CCSU without coming clean about Edward Clarkin and several other things, so he wrote an email on Dec. 23 to the head of the journalism department “expressing concern toward Schroeder teaching this spring.” He got the other editors of the student newspaper, the Recorder, to sign it.

According to Vivian Martin, chair of the journalism department, the situation with Schroeder “was monitored and discussed with others within the university as the story mounted.” Martin told me she called a meeting with faculty, students and Schroeder on December 30, which is during the break between semesters. Because it’s a personnel matter she could not go into much detail. “We can’t just fire [someone] based on newspaper stories,” she said. (This is true: university administrators are told to step very carefully around personnel decisions.)

According to Marinelli, the students were vocal and united. They wanted him to apologize publicly for his behavior and accept that he had made serious mistakes. He refused. “We felt that the standards of journalism had been violated by the plagiarism and fabrication of detail and quotes,” Marinelli told me. They also wanted Schroeder to say once and for all who ‘Edward Clarkin’ was. “Because we did not find a common ground of him giving us any clarity, we did not want him to teach at Central.” Marinelli said the original intent of the letter was not to get anyone fired. They just wanted a public apology and a fuller explanation.

Instead, Schroeder resigned a few hours after the December 30 meeting.

“Hats off to the student editors who challenged Mike,” said Jim Smith, who was there. He has worked for Schroeder and in a long career edited other newspapers in Connecticut. (He agreed to teach the spring semester course Schroeder was going to teach.) Smith told me that Schroeder was challenged at the meeting to come clean about all the major questions that people following the story have: not only ‘who is Edward Clarkin?’ but the nature of Schroeder’s relationship to Sheldon Adelson and why the disputed article was published at all.

“The students were extremely upset about this huge breach of trust for an publisher and editor,” he said. “They didn’t want him to take the teaching position and sully the reputation of the school they were graduating from.” He added that in his view Schroeder made a mistake with the Edward Clarkin article, but he has also done a lot of good for journalism in central Connecticut. “The Bristol Press and the New Britain Herald wouldn’t exist today without Mike,” Smith said. “He saved two newspapers.”

Six days after the meeting at Central Connecticut State, Schroeder put into print a kind of a mea culpa. His “note to readers” does not — in my view — take any real responsibility for his actions or explain what his motivations were. (My analysis is here.) But it was better than nothing.

Many people watching this story have assumed that ‘Edward Clarkin’ is in fact Schroeder. And there is no doubt that he is author of the act. He admitted as much in his note to readers. But he told the Connecticut State students that the author of the article was a freelance writer, a person he would not identify. Schroeder said he edited the piece, and of course directed that it be published, which is what I mean by author of the act.

Here he may be telling the truth. We know Schroder tried to get another freelancer to take on the assignment. He has reason not to name the original author, because reporters would no doubt contact that person in an attempt to learn more about Schroeder’s machinations. He can say he’s trying to save the freelancer from the glare of publicity while protecting his own backside.

So it was smart of the Connecticut State students to demand clarity on Edward Clarkin. It was an inspired act by Chris Marinelli to organize the student editors to express their concerns. And it’s good for CCSU that Vivian Martin intervened, because it led to the right outcome. After all, the Review-Journal in Las Vegas recently called Schroeder the “disgraced Connecticut newspaper owner associated with casino mogul Sheldon Adelson.” That’s not someone you want on your faculty.

January 27 at 8:00pm

I have published a new post on all this that I worked very hard on. It lays out my hypothesis for what happened. The new post is called: Journalists as ‘hit squad:’ Connecting the dots on Sheldon Adelson, the Review-Journal of Las Vegas and Edward Clarkin in Connecticut. Please read it. In a coda the end, I draw this depressing conclusion:

Most likely, we will never find out what happened, unless the national press makes a continuing and big deal out of it. But with no new information to report, the chances of that happening are thin. So in all probability, the attempted misuse of journalists as a ‘hit squad’ will go unexplained and unexposed. That’s frustrating. If David Carr were still alive, I would be sending this note to him. Instead, I am publishing it. But I do not have much hope that it will make a difference. Chances are no one will pay. It appears they got away with it.

January 28 at 6:10pm.

News from Las Vegas: Jason Taylor, publisher of the Review-Journal, is out. (He’s one of the five men who know, as I put it here.) Taylor was replaced today by Craig Moon, former publisher of USA Today, who left that job 2009. There was an all-hands meeting where Moon was introduced. According to what I learned from GateHouse employees and this AP report, Jason Taylor will stay with GateHouse in an executive capacity overseeing Western properties. New publisher Craig Moon will not be a GateHouse person, as Jason Taylor was, but an employee in the House of Adelson.

“It wasn’t immediately clear what prompted the change in leadership,” the New York Times wrote.

This development changes the executive picture, and indicates tightening control over the Review-Journal by the Adelson forces. Meanwhile, at the centralized print production center in Austin, GateHouse employees were told by Senior VP David Arkin that as of March 1 they will no longer be composing the pages of the Review-Journal. So the “divorce” between GateHouse and the Adelsons is being finalized. Also, from sources in the Review-Journal newsroom: the disclosure statement that used to run on page 3 of the print edition and the home page of the digital edition is no more, on orders of the new publisher:

It seems like the noose is tightening in the Review-Journal newsroom. Another indication of that: I’m told that at the all-hands meeting in Las Vegas to introduce the new publisher, no one even asked about the events of December and whether lingering questions around the judges investigation would ever be addressed. On the surface all is sunny however: This passage ran in the Review-Journal:

Moon said Sheldon Adelson asks insightful questions about newspapers. Adelson owns Israel Hayom, an Israeli newspaper.

“Sheldon is pretty articulate about things about newspapers, like: ‘So do you think the presses are being optimized?'” Moon said.

Moon said the owner puts the newspaper in a solid position for the future.

“I really do want to make this a world-class media business — the best it can possibly be,” he said. “We’ve got a great owner. We’ve got the commitment of a great owner. We’re not a public company having to sit and talk about how our earnings were the for the last quarter, and I think we’re going to be able to do some really big things here.”

UPDATE: Jan. 29: Things are coming into clearer focus now. The Review-Journal reports that Sheldon Adelson is trying to lure the NFL’s Oakland Raiders to Las Vegas by proposing to build an expensive new stadium, which is what it takes:

Casino giant Las Vegas Sands Corp. will lead a consortium of investors planning to build a $1 billion domed stadium on 42 acres near the University of Nevada, Las Vegas that would house the school’s football team — and possibly a National Football League franchise.

There are all kinds of ways that owning the largest newspaper in Nevada could be useful in trying to get a project like that done. For example, this from a Las Vegas Sands Corp spokesman: “Abboud said Las Vegas Sands may seek legislative approval for diversion of hotel room tax revenues that now support the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority to the project.” Adelson needs lots of people and public bodies to go along with his scheme if the stadium plan is to work. When you factor that in, owning the Review-Journal makes more sense.

That is exactly the theme of this column by Jon Ralston, the most prominent journalist in the state: Adelson begins to play with his new toy. It’s about aiding Adelson’s campaign for a new stadium through orchestrated coverage in the Review-Journal.

Also see Columbia Journalism Review: Review-Journal backtracks on ownership disclosure.

February 4 6:32pm.

Something without precedent in my experience — and in the memory of several media reporters I consulted — happened today. The CEO of a major newspaper company accused “disgruntled reporters” in one of that company’s newsrooms of telling “untruths” in their reporting. In a word, he said they were liars. Yes. You read that right. Unbelievable as it sounds (because what could be more damaging to a publicly-traded company than an admission like that?) this actually happened today.

As you might expect, the explanation is complicated. So bear with me…

In this post, I described in detail how GateHouse Media executives had failed to explain why they asked two different newsrooms inside their company (one in Sarasota, Florida, the other in Las Vegas) to investigate Nevada state judges. The question mattered because one of the Nevada judges who was “monitored” by GateHouse journalists, Elizabeth Gonzalez, presides over a sensitive and potentially damaging civil suit involving Sheldon Adelson. Adelson is the billionaire owner of Las Vegas Sands Corp, a major donor to Republican causes, and in December 2015 the stealth purchaser of the Las Vegas Review-Journal, largest newspaper in the state, which he bought from GateHouse Media for a price estimated at two to three times what the property was worth in strict market terms.

Why did Adelson, shrewd businessman that he is, overpay so dramatically for the Review-Journal? On the surface it appeared that in return for an inflated price for the R-J, GateHouse had agreed to use its newsroom resources to put a judge troublesome to Adelson under journalistic surveillance.

After these circumstances became known, the company failed to explain where the order to investigate the judge came from, what the logic of that assignment was, or how it originated. In published accounts, reporters at the Review-Journal in Vegas said they had been ordered to investigate the judge by GateHouse Media officials. When they asked for an explanation (what is this story about?) they received none— just orders to do as they were told. So they did what they were told. They “monitored” the judges for a week and submitted their notes to higher-ups, still confused about what they were doing and why.

Today Ken Doctor of Politico reported on an interview he secured with the man who is ultimately in charge: Mike Reed, CEO of the holding company for GateHouse Media. Reed told Doctor there had been on “ongoing” investigation of Nevada judges, into which the monitoring of judge Elizabeth Gonzalez naturally fit. The journalists at the Review-Journal deny this. They say they didn’t understand why they were being told by higher-ups at GateHouse to scrutinize the judges, including Gonzalez. They were simply ordered to do it, so they complied.

CEO Mike Reed disagrees with that. “There was no specific mandate that would say, ‘You do it or you are fired.’” But the assignment was agreed to and understood by the Las Vegas newsroom, he says.

Then this incredible passage appears in Ken Doctor’s account:

Reed contends, contrary to what journalists in the R-J newsroom have said both publicly and confidentially to me, that there was an “ongoing investigation” of the Las Vegas judiciary.

“I’m on the record in the New York Times saying the investigation was ongoing.”

I told Reed I had talked to a number of journalists at the R-J, who all said the one-week judge review had ended in November.

“A lot of media people have been spun by untruths spun in that newsroom…. Like many things that came out of disgruntled reporters in Las Vegas, there were many untruths.”

There it is. Boss of a major newspaper company, publicly traded, says that “disgruntled” reporters who used to be part of his company are spinning, lying, publicly spouting untruths. That is amazing. It is roughly equivalent to the CEO of a major auto company like Volkswagen calling its own engineers liars. Think about what that means for the firm’s reputation. If it’s true it’s hugely damaging. If it’s false it’s even more damaging.

My conclusion: Mike Reed, CEO of New Media Investment Group, holding company for GateHouse Media, had no idea what he was up to when he publicly denounced the Review-Journal newsroom as liars. He was out of control, out of his depth, unaware of the consequences of what he was saying. Today we saw a public meltdown at the top of the company that owns or controls more news sites than any other in the United States.

February 8 at 11:15pm

Many strange things have happened since I have been following the story of Sheldon Adelson’s stealth purchase of the Las Vegas Review-Journal, but that doesn’t mean they can’t get stranger. They can. And the other day they did.